Jump back to chapter selection.

Table of Contents

1.1 Maxwell's Equation of Macroscopic Electromagnetism

1.2 Travelling-Wave Solution

1.3 The Dispersion of the Free Electron Gas and Volume Plasmons

1.4 Real Metals and Interband Transitions

1.5 The Energy of the Electromagnetic Field in Metals

1 Electromagnetics of Metals

The interaction of metals with electromagnetic waves can be understood in a classical framework based on Maxwell's equations. This holds true even for metallic nanostructures down to sizes on the order of a few nanometres, without the need to resort to quantum mechanics. This is because the high density of free carriers results in narrow spacings of the electron energy levels compared to the thermal excitation energy

In this low-frequency regime, the perfect conductor approximation of infinite or fixed finite conductivity is valid for most purposes since only a negligible fraction of the impinging electromagnetic waves penetrates the metal. However, at higher frequencies approaching the near-IR and visible spectrum, field penetration increases significantly. At UV frequencies, metals acquire a dielectric character and allow the propagation of electromagnetic waves, albeit with varying degrees of attenuation depending on the details of the electronic band structures. Alkali metals, such as sodium, have an almost free-electron-like response and thus exhibit ultraviolet transparency. Noble metals, such as gold and silver, exhibit strong absorption in this regime due to transitions between electronic bands.

1.1 Maxwell's Equation of Macroscopic Electromagnetism

These dispersive properties can be described by a complex dielectric function

As a starting point, recall Maxwell's equations of macroscopic electromagnetism:

These equations link the four macroscopic fields:

- The dielectric displacement

, - The electric field

, - The magnetic field

, - The magnetic induction (or magnetic flux density)

with the free charge and current densities

We distinguish between free (

and

The four macroscopic fields are further linked via the polarisation

where

Charge conservation (

The great advantage of this approach is that the macroscopic electric field includes all polarisation effects: in other words, both the external and induced fields are absorbed into it:

Limiting ourselves to linear, isotropic, and nonmagnetic media, one can define the constitutive relations:

Here,

The last important constitutive linear relationship to mention is that between the free current density

It should be noted that the linear relations for

for a given wave vector

and

are complex-valued functions of angular frequency

Explicitly, this leads to the components of the dielectric function:

Here,

Therefore, the imaginary part

1.2 Travelling-Wave Solution

When studying the propagation of wave in vacuum, the focus is always on transverse waves, as longitudinal solutions do not exist . This is no longer the case in a medium. Plasmons are longitudinal solutions of the Maxwell equations. By considering the propagation of coupled mechanical and electromagnetic waves, the electromagnetic solution has an electric parallel to the wavevector. More generally, this solution is a longitudinal solution with

Therefore, such an equation is fully described by

Let us examine the existence of a longitudinal solution of Maxwells equation without invoking a specific model of the medium. We will only assume, as always, a linear, homogeneous and isotropic medium, such that we can use the dielectric function:

Note that the frequency dependence of the dielectric function is called dispersion, while its dependence on the wavevector is called spatial dispersion. By considering the relation in real space, and invoking the zero divergence of the displacement field, we find that we can differentiate two cases:

-

Longitudinal waves: Seeking a non-zero longitudinal electric field, we impose

This then leads to which can be further simplified to

for a local medium. This signifies that longitudinal collective oscillations can only occur at frequencies corresponding to zeros of . Indeed, one such solution is in the case of a non-lossy Drude model. Keep in mind, neglecting the -dependence typically holds well for The Drude model is inherently a local model, that makes this assumption. -

Transverse waves,

, resulting in the generic dispersion relation:

1.3 The Dispersion of the Free Electron Gas and Volume Plasmons

Let us discuss the transparency regime

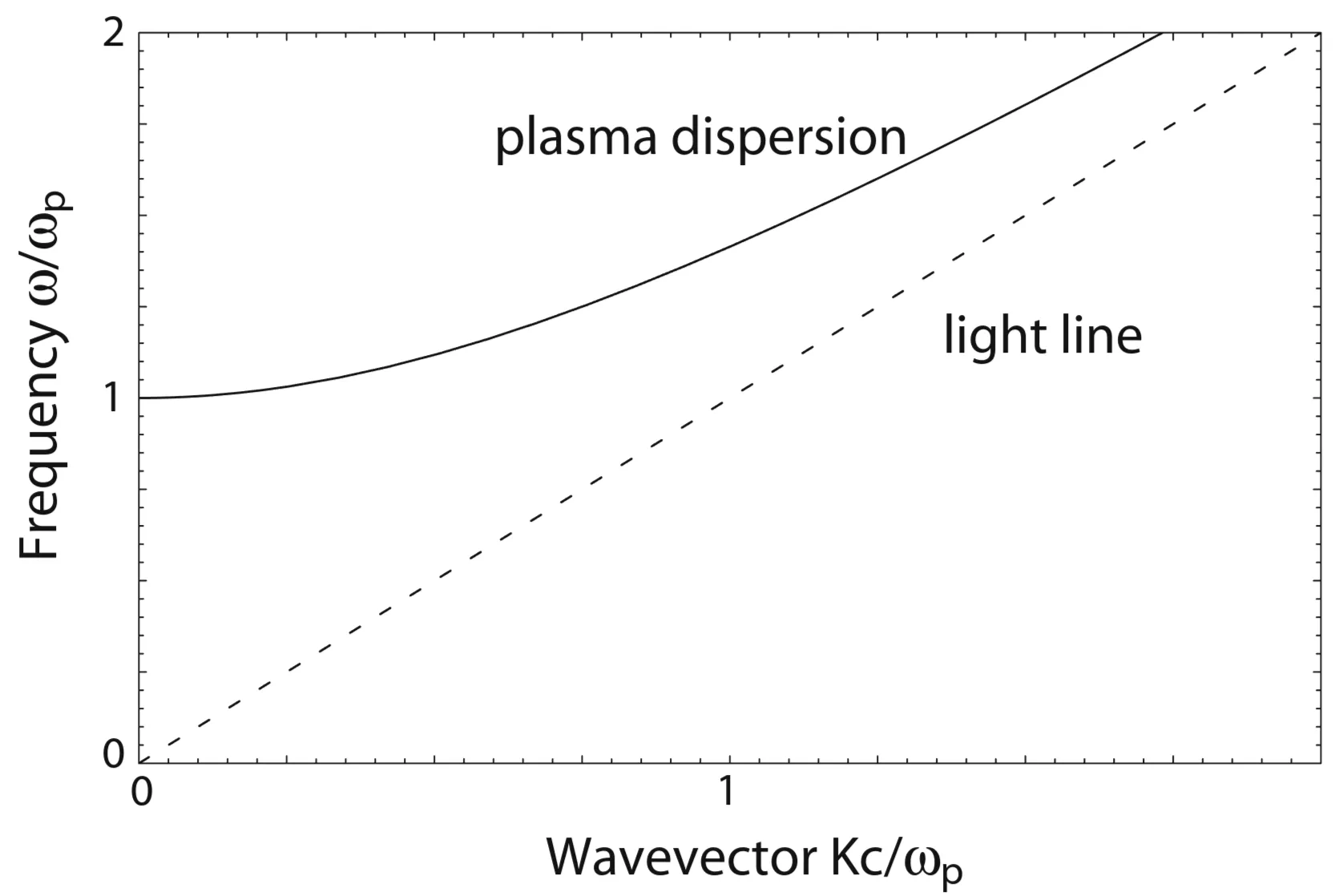

This relation is plotted here:

For frequencies below the plasma frequency, the propagation of transverse electromagnetic waves is forbidden inside the metal plasma. For larger frequencies, however, the plasma supports transverse waves propagating with a group velocity

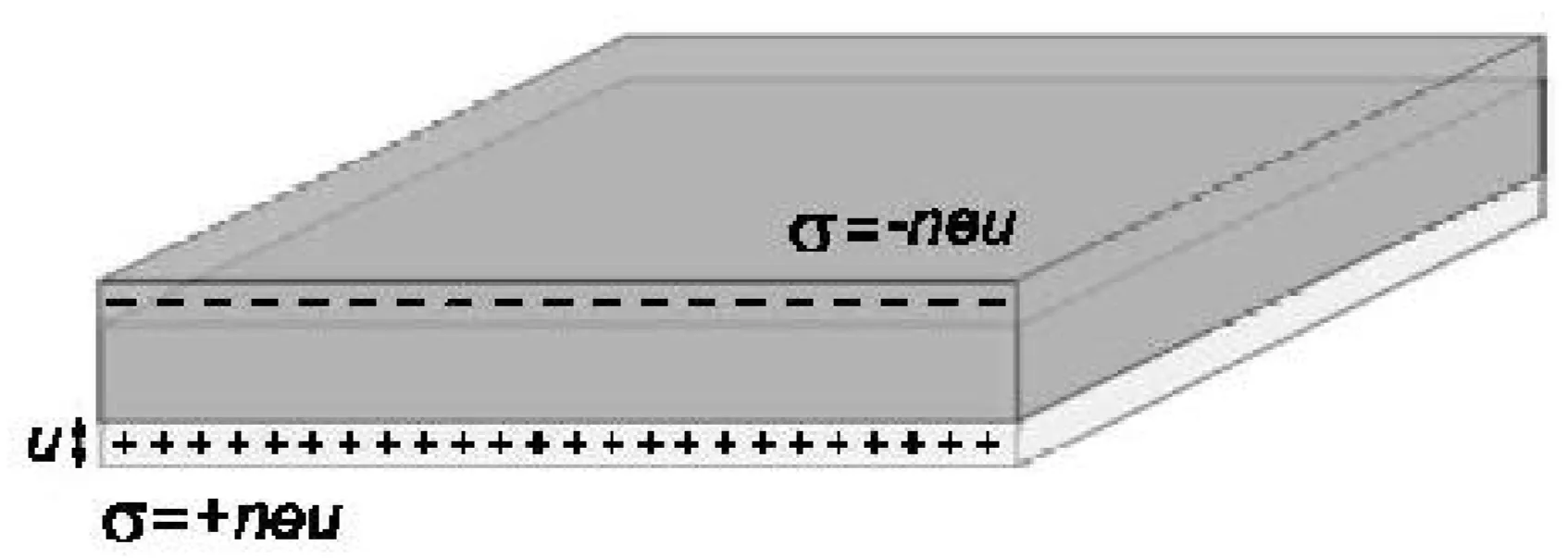

The physical significance of this excitation at the plasma frequency can be understood by considering the collective longitudinal oscillation of the conduction electron gas against the fixed positive background of the ion core in a plasma slab:

A collective displacement of the electron cloud leads to a surface charge density at the slab boundaries. This establishes a homogeneous electric field inside the slab. Therefore, the displaced electrons experience a restoring force, and the plasma frequency is the natural frequency of a free oscillation of the electron sea. This assumes all electrons move in phase, meaning the plasma frequency corresponds to the oscillation frequency in the long-wavelength limit where

The quanta of these charge oscillations are called volume plasmons, to distinguish them from surface and localised plasmons. Due to the longitudinal nature of the excitation, volume plasmons do not couple to transverse electromagnetic waves and can only be excited by particle impact. Another consequence of this is that their decay occurs mainly via energy transfer to single electrons in collisionless plasmas, a process known as Landau damping.

In addition to the in-phase oscillation at

1.4 Real Metals and Interband Transitions

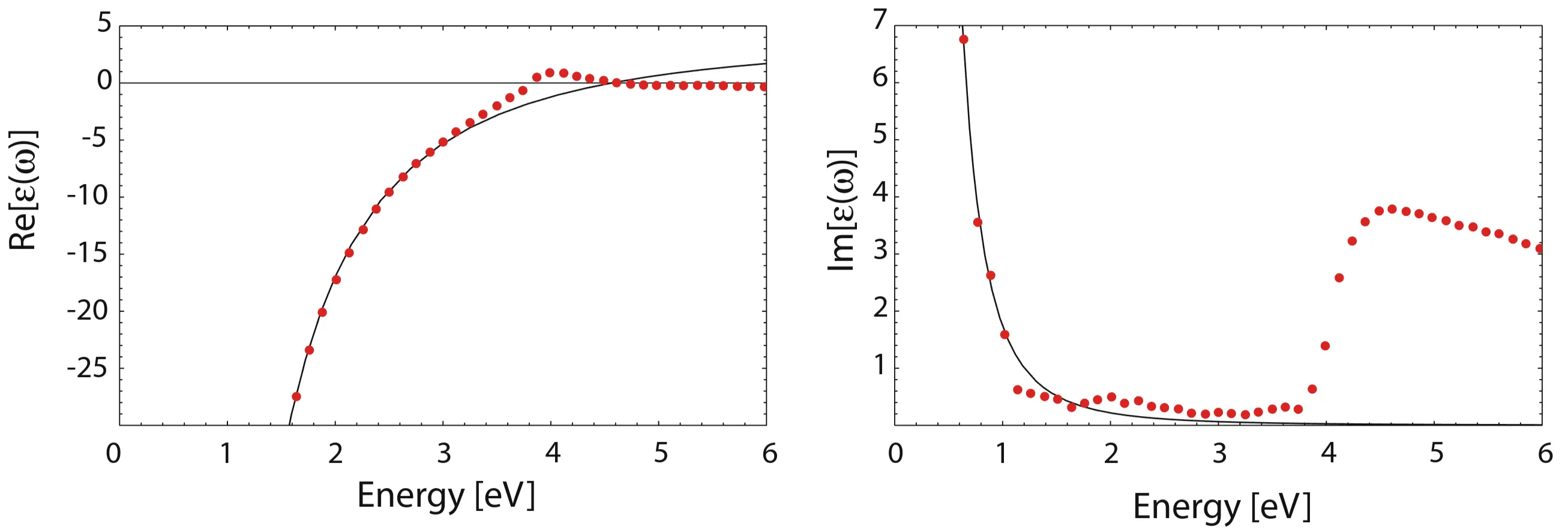

As already mentioned, the dielectric function of the Drude model adequately describes the optical response of metals only for photons below the transition energy between electronic bands. For some noble metals, interband effects already occur around

The red dots are experimentally obtained results, while the line is a fit of the Drude model. Clearly, the model is not adequate to describe either the real or imaginary part of the dielectric function at high frequencies, and in the case of gold, its validity already breaks down close to the visible range.

1.5 The Energy of the Electromagnetic Field in Metals

For a linear medium with no dispersion or losses, the total energy density of the electromagnetic field can be written as:

This expression, together with the Poynting vector of energy flow

relating changes in electromagnetic energy density to energy flow and Ohmic losses (work done by the field on free charges) inside the material.

However, in metals, the dielectric function

A more general expression for the time-averaged electric energy density in a dispersive, low-loss medium, when the electric field

where

However, the electric field energy can also be determined by explicitly considering the electric polarisation. For a material described by a free-electron-type (Drude model) dielectric function

where