Jump back to chapter selection.

Table of Contents

2.1 Soliton modelocking

2.2 Saturable Absorbers and Passive Modelocking

2.3 Power Spectral Density, Relative Intensity Noise, and Signal-to-Noise Ratio

2.4 Noise of Modelocked Lasers

2.5 Shot Noise in Lasers

2.6 Influence of Spectral Broadening on Noise

2.7 Using Noise Gain from Spectral Broadening to Infer a Low Shot-Noise Level

2 Theory

2.1 Soliton modelocking

Soliton modelocking is a frequently used method to produce ultrashort pulses utilising the formation of solitons. When the effects of self-phase modulation (SPM) and negative group delay dispersion (GDD) balance, a soliton pulse is formed, which can propagate without pulse or spectral broadening in a dispersive medium. This balance is self-stabilising: since SPM depends on peak power while GDD does not, deviations in pulse parameters tend to be corrected, leading to a stable solution. This inherent stability makes solitons robust against distortions.

The starting point for any discussion on solitons is that they are the fundamental solution to the nonlinear Schrödinger equation (NLSE)

where

The fundamental soliton has the form

with

where

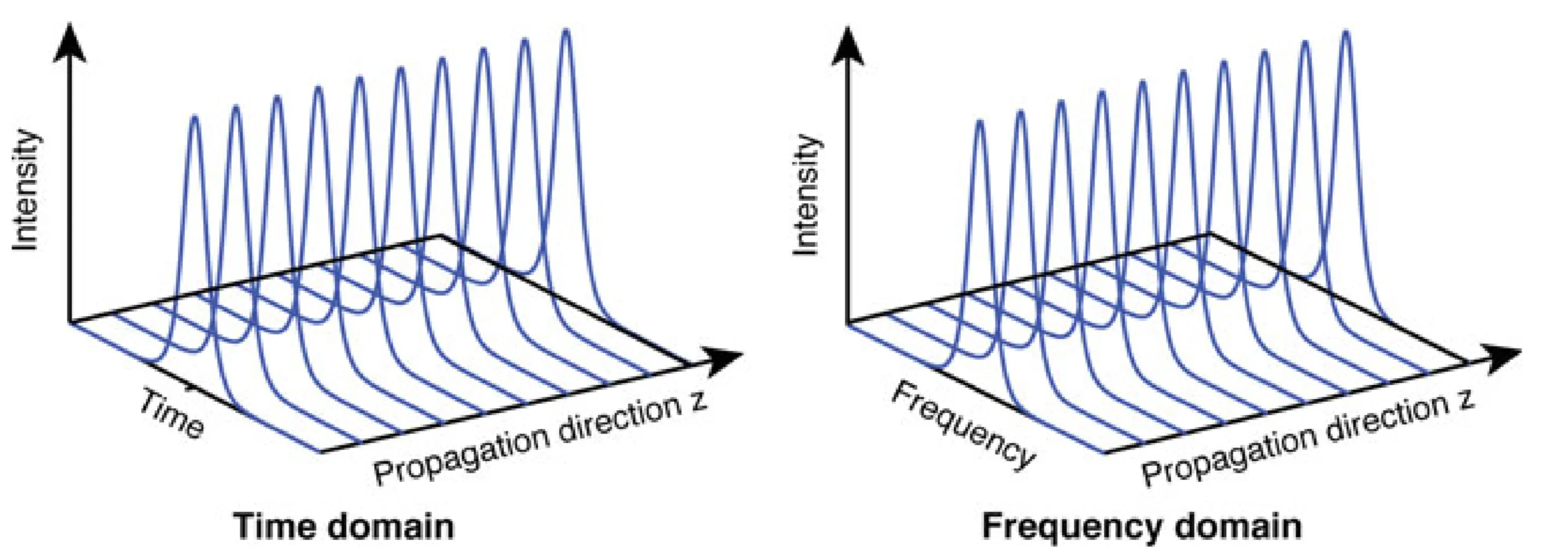

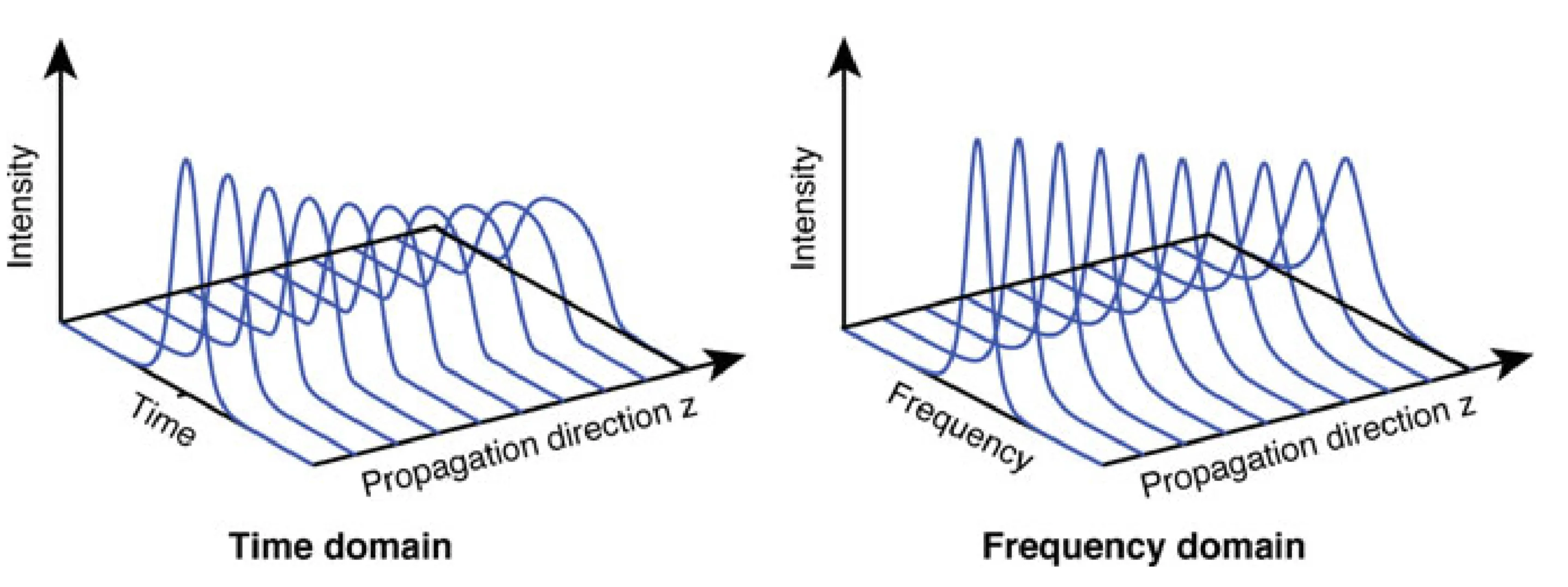

The following two figures compare the cases of negative and positive SPM, showing how positive GDD requires negative SPM to create a soliton.

A soliton can only form if the SPM has the opposite sign of the GDD. In this case, positive GDD requires negative SPM for a stable wavepacket (a soliton) to form. The shape remains unchanged in the time and frequency domain.

Positive SPM amplifies the broadening effect of the already positive GDD. A soliton cannot form, and the pulse will keep broadening.

It is important to note that the preceding discussion assumes a uniform distribution of SPM and GDD. However, in practice, this uniformity is not always maintained within the laser cavity. Consequently, the pulse shape is only fully restored after a complete roundtrip through the cavity. During this roundtrip, the pulse may deviate from its ideal form, leading to temporary distortions.

2.1.1 Periodic Perturbations of Solitons

In lasers, solitons within the cavity are subjected to recurrent perturbations, such as those due to losses at the output coupler. Consider a soliton experiencing periodic perturbations within a system, represented by:

where

From the nonlinear Schrödinger equation, incorporating the periodic perturbation gives:

where

where

Neglecting higher-order terms, the equation simplifies under the assumption

The periodicity introduces the possibility of resonance, where the perturbation frequency aligns with the natural frequencies of the system, potentially leading to significant growth in the amplitude of

where

Under this condition, the perturbation behaves almost as if it were continuous, allowing us to treat it with standard perturbation techniques.

2.2 Saturable Absorbers and Passive Modelocking

Until now, modelocking has been primarily explained through the nonlinear Schrödinger equation, highlighting the balancing effects of group delay dispersion and self-phase modulation. While the NLSE provides a powerful framework for understanding the formation and stability of soliton pulses, it does not fully capture all aspects of the laser dynamics. Specifically, the influence of gain, loss, and the initial pulse formation within the laser cavity are not addressed. In this section, passive modelocking is described from the perspective of saturable absorbers, such as the SESAM, with a particular focus on the formation of pulses.

The primary function of a saturable absorber (SA) is to implement self-amplitude modulation (SAM): it induces high losses for low-intensity light and low losses for high-intensity light. This results in loss modulation, as the pulse peak saturates the absorber more strongly than its wings. The starting point is the equation for the saturable loss coefficient:

where

where

In discussing passive modelocking, three cases are typically distinguished: (1) A slow saturable absorber with dynamic gain saturation, (2) a fast saturable absorber, or (3) a slow saturable absorber with no dynamic gain saturation. The last case is commonly referred to as soliton modelocking. The SESAM in this thesis operates in this regime as a slow, saturable absorber. To account for aspects such as gain and loss, the starting point is the Haus Master equation:

which holds at steady-state over a "long" timescale

Here,

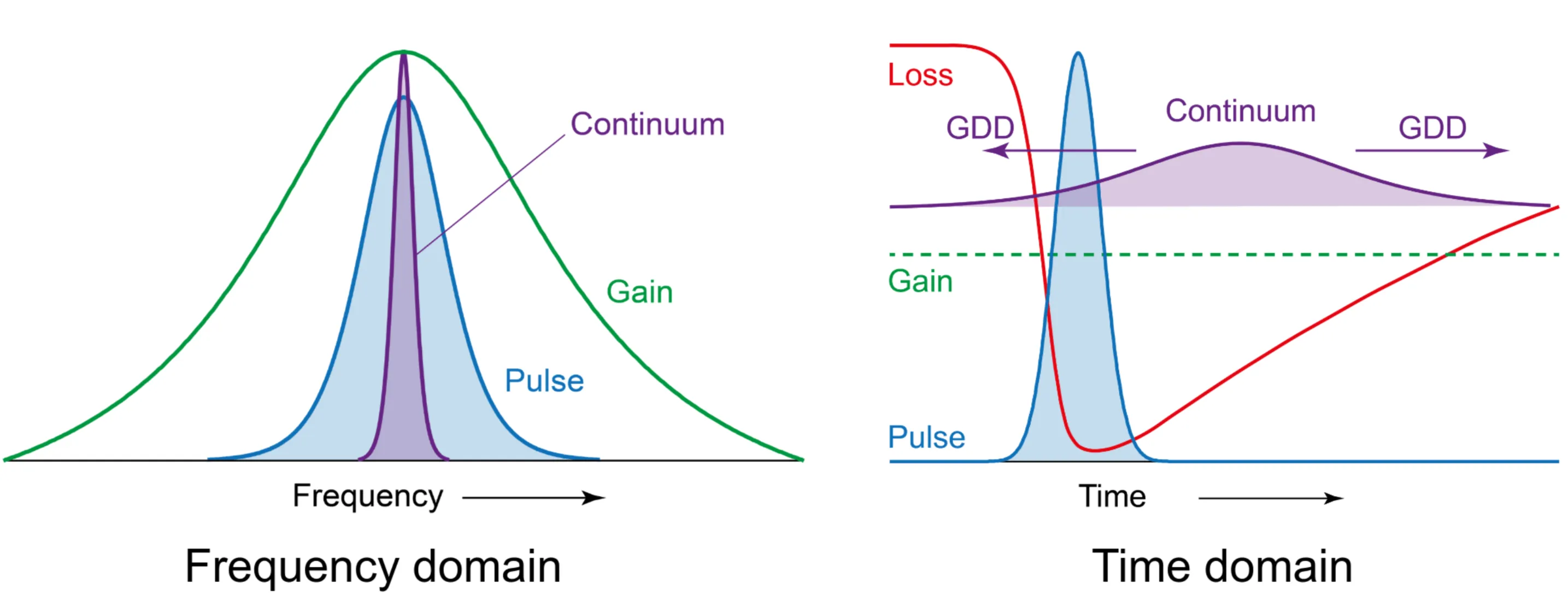

Illustration of soliton modelocking with gain and loss dynamics. The main soliton pulse (left) is stabilised by the interplay of gain and saturable absorption, while a weak, temporally spread-out continuum (right) is suppressed due to low intensity and the absence of self-phase modulation (SPM). The slow saturable absorber prevents the continuum from reaching the gain threshold, thereby maintaining a stable pulse within the laser cavity.

Due to its low intensity, the continuum does not experience SPM, resulting in its spread over time due to GDD (as shown on the right side of the previous figure). Because it is spectrally narrow, it experiences high gain. The slow SA is still fast enough to ensure that the continuum experiences enhanced losses, preventing it from reaching the threshold where gain equals losses. This stabilisation mechanism gradually removes the continuum or noise, thereby stabilising the soliton pulse. This explains how passive modelocking produces stable pulses despite the presence of the continuum. Passive modelocking ideally starts from noise fluctuations within the laser, where a noise spike is amplified more than other fluctuations until it reaches a steady state.

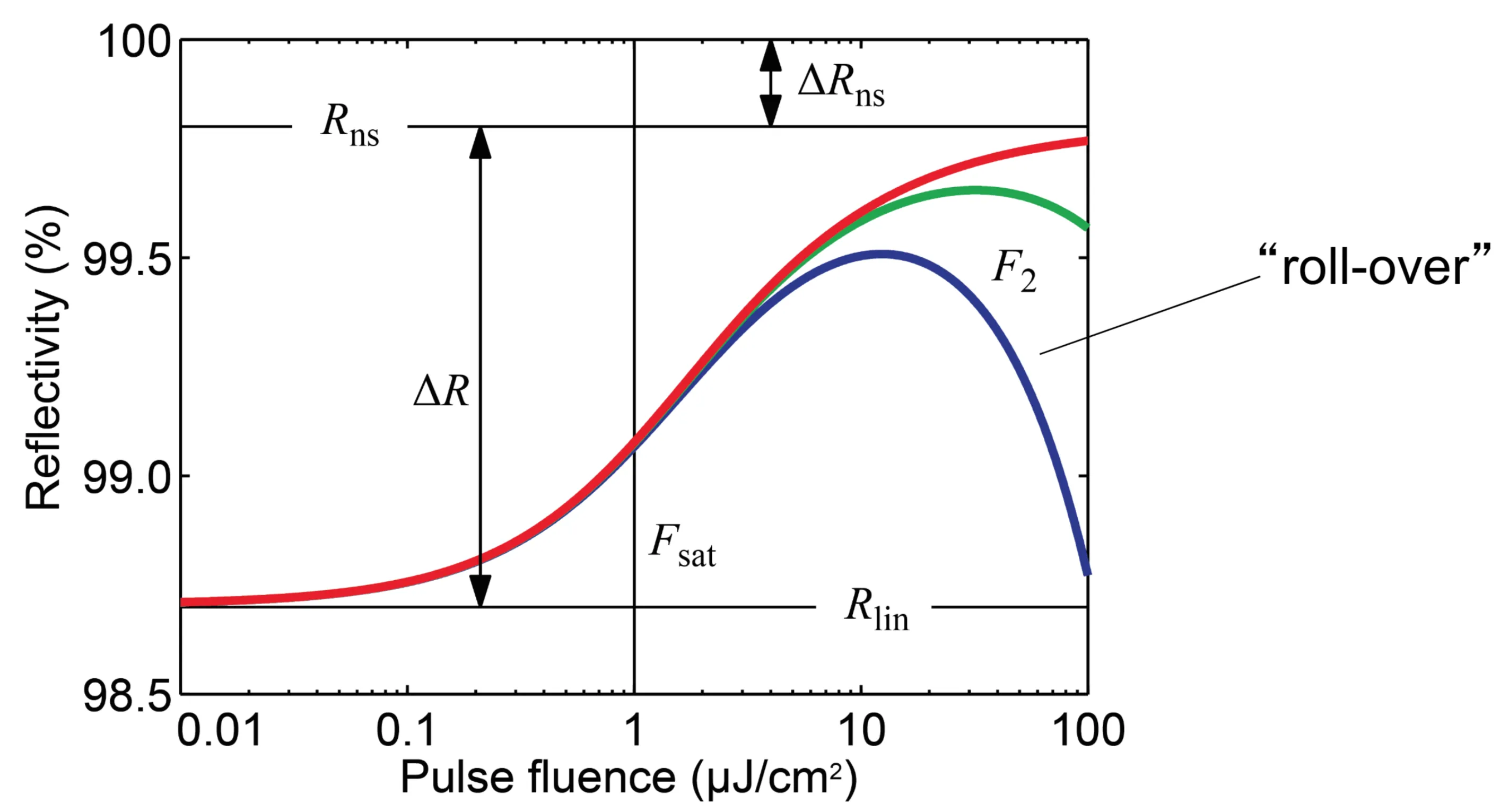

As mentioned, the SESAM used in this thesis is a slow, saturable absorber. The next figure depicts the reflectivity behaviour as a function of the incident fluence:

As expected, the reflectivity initially increases with increasing fluence. However, eventually, the reflectivity decreases again due to second-order processes such as two-photon absorption. This leads to a rollover in the curve, typical of SESAMs, and is also called inverse saturable absorption.

2.3 Power Spectral Density, Relative Intensity Noise, and Signal-to-Noise Ratio

This section delves into several fundamental concepts essential to this thesis, including signal processing and optical communication: Power Spectral Density, Relative Intensity Noise, and Signal-to-Noise Ratio. To avoid confusion between various notations, this thesis adheres to the IEEE standard on random instabilities.

2.3.1 Power Spectral Density

The power spectral density (PSD) is a measure of the power content distributed across different frequencies within a signal. To illustrate, consider a general signal

In the context of digital signal processing, the energy

From Parseval's theorem, we further find that the energy in time is equal to the energy in frequency:

where

Therefore, power is simply energy divided by time:

It is natural to define the energy spectral density as

and consequently the (one-sided) power spectral density (PSD) for a stationary stochastic process

The units of PSD are

Another useful result comes from the Wiener-Khinchin theorem, stating that the power spectral density is the Fourier transform of the autocorrelation function

By applying the Wiener-Khinchin theorem, we can utilise autocorrelation measurements – often more straightforward to obtain experimentally – to derive the PSD. This is particularly useful in intensity noise measurements, where the autocorrelation function of the laser's intensity fluctuations is recorded over time. By transforming this autocorrelation data using the Wiener-Khinchin theorem, we can determine the PSD of the noise.

2.3.2 Relative Intensity Noise

Relative Intensity Noise (RIN) quantifies the intensity fluctuations of a signal relative to its mean intensity. For a signal

where the units are

The total PSD of the signal can be decomposed into the PSD of its mean and the PSD of its fluctuations:

where

2.3.3 Signal-to-Noise Ratio

The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a critical metric for evaluating the quality of a signal. It quantifies the ratio of the power of the signal to the power of background noise:

where

It is essential to specify these frequency limits because the variance, or root mean square (RMS) value, of the signal's fluctuations

2.4 Noise of Modelocked Lasers

As this work primarily concerns noise, it is essential to discuss the noise characteristics of modelocked lasers. When light intensity

Therefore, the detector captures intensity noise originating from shot noise, Johnson (thermal) noise, and excess laser noise.

2.4.1 Noiseless Modelocked Laser Intensity

We begin with the intensity of an ideal, noiseless modelocked laser, which can be described by a delta-comb function:

where

2.4.1.1 Timing jitter

Any fluctuation in the optical path length results in timing jitter, as the repetition frequency is the inverse of the cavity round-trip time. Timing jitter

which shifts the temporal position of each comb line. This transforms the PSD of the ideal comb into:

The scaling goes as

When considering limits, we obtain:

where the index

2.4.1.2 Intensity noise

Normalised intensity noise is a significant type of noise in modelocked lasers. It is important to note that intensity noise and phase noise are often closely related, as the same underlying noise sources can induce both through coupling effects. Its effect changes the intensity as

The corresponding PSD is:

which, in contrast to timing jitter PSD, is independent of the harmonic order

However, it is crucial to note that calculating this standard deviation without specifying frequency boundaries is not just less meaningful; it is effectively meaningless. The standard deviation must always be provided with well-defined frequency limits for accurate and practical measurements. This ensures that the noise characteristics are appropriately quantified and relevant to the specific application or measurement scenario:

where

2.5 Shot Noise in Lasers

Shot noise is a fundamental type of noise in electronic and optical devices, arising from the discrete nature of charge carriers (electrons) and light (photons). In lasers, shot noise is a consequence of the quantum statistical nature of photon emission. Although photon emission in lasers primarily occurs through stimulated emission, which leads to correlated emission events, the underlying processes are inherently probabilistic. The random nature of these processes, which follow a Poisson distribution, results in intrinsic fluctuations in the number of photons detected over a given interval. These fluctuations are inherent to the light itself, regardless of the stability of the light source.

For a photodiode detecting light, the photocurrent

where

According to Schottky's theorem, the power spectral density (PSD) of shot noise in the photocurrent is given by:

which highlights the frequency independence of shot noise, classifying it as white noise. A derivation of this theorem is provided in the Appendix. The PSD of shot noise related to optical power fluctuations can also be expressed as:

where

Using the definitions above, the Relative Intensity Noise for shot noise can be expressed as:

From these results, we can deduce the following behaviour: Attenuating the laser output increases the relative intensity noise (RIN) due to shot noise. This is because reducing the power of a coherent beam makes quantum fluctuations more significant relative to the signal. Conversely, increasing the power reduces the relative impact of shot noise as the signal strength increases; however, this also increases the absolute level of shot noise due to the higher photon count. Additionally, increasing the bandwidth increases shot noise power, as more noise fluctuations are detected within the broader frequency range. Detector efficiency is also crucial: lower efficiency leads to fewer detected photons, which may reduce the absolute shot noise but increase the relative shot noise per detected signal, thereby degrading the signal-to-noise ratio.

While shot noise tends to dominate at high frequencies, the specific frequency at which this occurs can vary widely depending on the laser architecture, gain medium, and other factors. For instance, in solid-state lasers, shot noise may become significant at frequencies around

At lower frequencies, various other noise sources become significant, including relaxation oscillations, pump noise, thermal noise, and

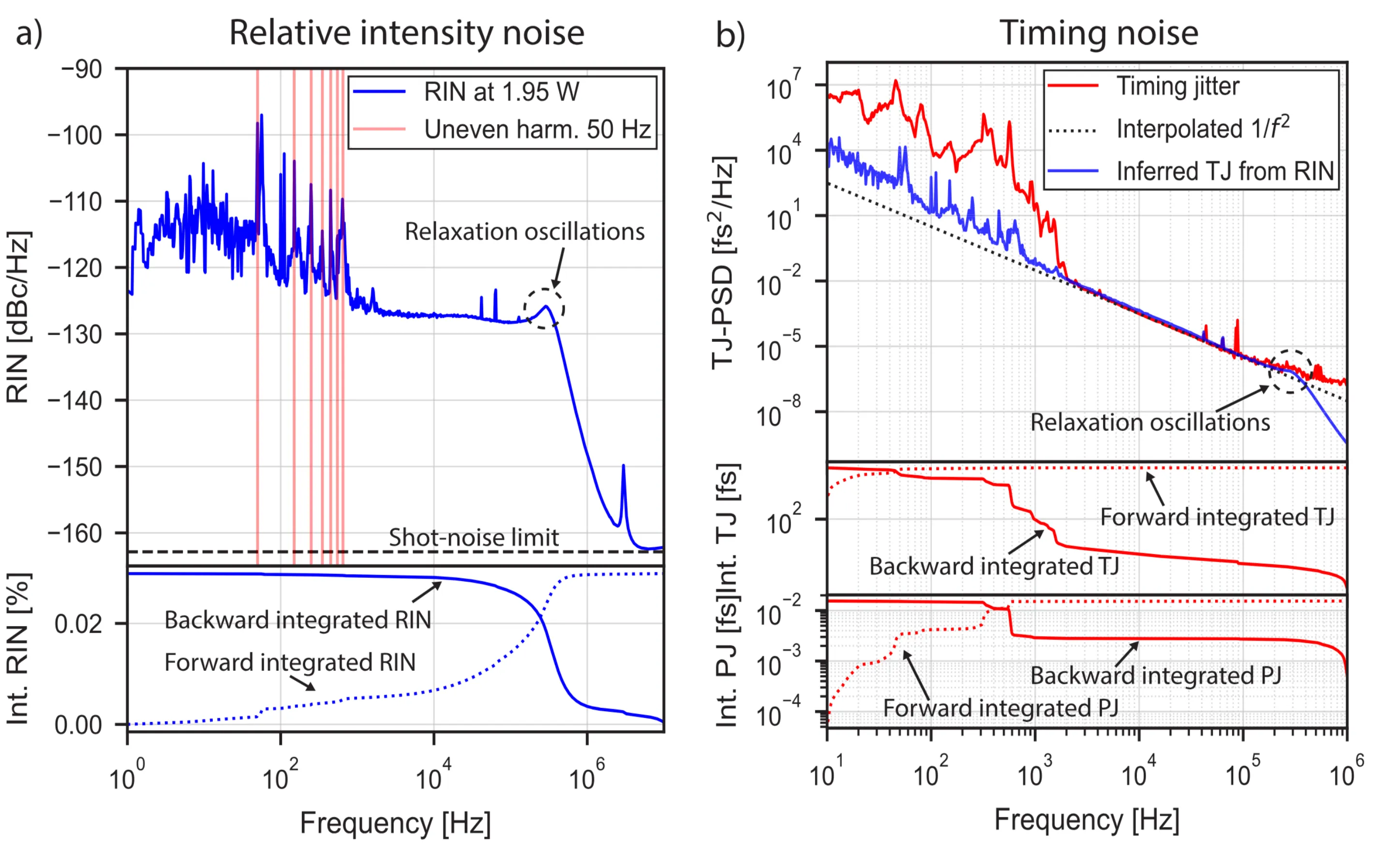

Relative intensity noise (RIN) and timing noise characteristics of a SESAM modelocked Ytterbium-doped solid-state laser operating at a GHz repetition rate. The figure illustrates various noise sources, with relaxation oscillations appearing as a prominent peak at lower frequencies. At higher frequencies, the noise level approaches the shot noise limit, indicating the dominance of quantum noise in this region.

A detector is said to be "shot noise-limited" when the predominant noise source affecting its performance is shot noise rather than thermal or electronic noise. In such systems, improving the SNR primarily involves increasing the optical power, as shot noise power scales linearly with optical power, while the signal power scales quadratically with optical field or linearly with optical power, leading to SNR improvements. Achieving shot noise-limited performance is desirable in applications requiring high precision and sensitivity, such as quantum optics and spectroscopy.

2.6 Influence of Spectral Broadening on Noise

Spectral broadening is a significant nonlinear optical effect utilised in various applications, such as supercontinuum generation, pulse compression, and potentially in enhancing noise measurement techniques. During spectral broadening, noise is influenced. In the frequency range where shot noise is the dominant noise source of the unbroadened laser system, spectral broadening can cause an increase in the noise PSD.

This section explores the potential of using spectral broadening to influence noise, particularly emphasising the Kerr effect in high-pressure Xenon gas-filled hollow-core fibres. While not traditionally associated with noise measurement, this approach offers a novel perspective on how nonlinear effects can interact with and potentially manage different noise contributions in optical systems.

2.6.1 The Optical Kerr Effect

The optical Kerr effect causes the refractive index of a material to become intensity-dependent. To the first order, this can be expressed as:

where

with

indicating that SPM broadens the bandwidth of a pulse. In the leading edge of the pulse, where

Various methods exist for spectral broadening, including the previously discussed self-phase modulation resulting from intensity-dependent phase shifts. Additionally, cross-phase modulation, four-wave mixing, Raman scattering, and supercontinuum generation are significant contributors to spectral broadening. Spectral broadening has applications in optical communication, metrology, and microscopy, among other fields.

2.6.2 Simulation

In the experiment, we utilise a high-power laser and high-pressure Xenon gas, chosen for its large nonlinear refractive index of

2.6.3 Laser Propagation in a Fibre: Split-Step Method

When analyzing the propagation of a laser pulse through an optical fibre, it is crucial to predict the output characteristics of the pulse, such as average power, pulse length, and spectral width, given specific input conditions. The nonlinear Schrödinger equation (NLSE) must be solved, which is inherently challenging due to its nonlinearity and complexity.

One of the most effective numerical techniques for solving the NLSE is the Split-Step method. This elegant approach allows the equation to be solved approximately by separating the linear and nonlinear components. It involves computing the solution in small steps, treating the linear and nonlinear effects alternately and independently. The linear propagation is performed in the frequency domain, while the nonlinear propagation is executed in the time domain, necessitating repeated Fourier transforms between these domains.

The starting point is the NLSE:

which can be rewritten in a more compact form for propagation over a small step

Here,

Although the linear and nonlinear parts have analytical solutions when considered independently, the full NLSE does not. The critical assumption of the Split-Step method is that the optical field's dispersive and nonlinear effects can be treated separately when propagating a small distance

which is generally only true for commuting operators. The assumption is that the nonlinear part acts first, followed by the linear part. Due to the BakerHausdorff formula, this method is accurate to the second order in the step size

This can be seen by replacing

Thus, the linear propagation over a small step

By combining the linear and nonlinear propagation steps, we obtain the overall solution over a small distance

where

2.6.4 Simulation predictions

To understand how intensity fluctuations of the laser influence the spectral broadening, the output spectrum of the fibre at

Moreover, since fluctuations in power also cause changes in pulse width and peak power, this effect should be considered in the simulation. Any approach should be consistent with the following relationship for average power

where the dependence of peak power

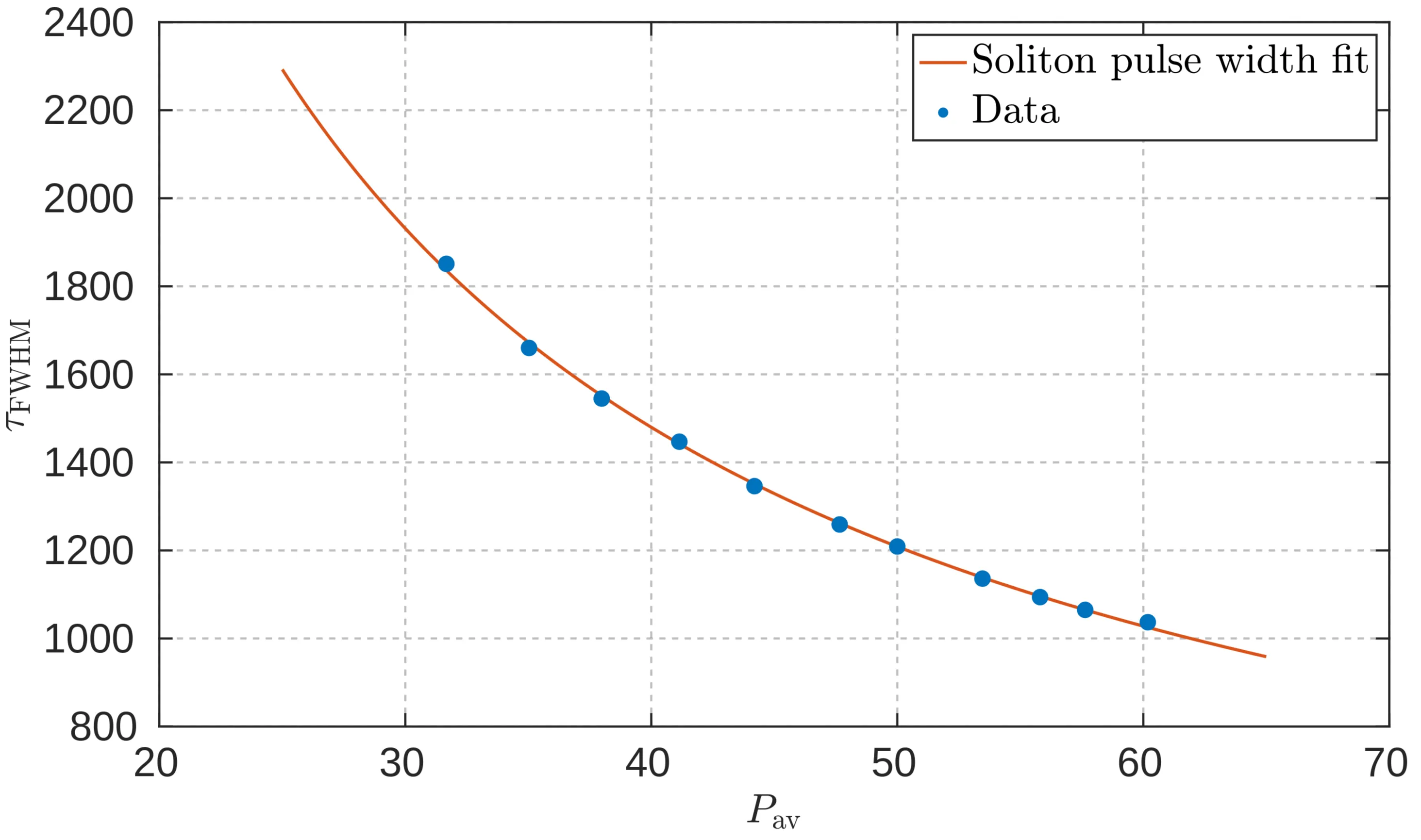

The next figure shows the measured pulse width for average laser output powers ranging from

Measured pulse width as a function of average laser output power, fitted with an inverse power law

As the soliton FWHM pulse width follows the relationship

where

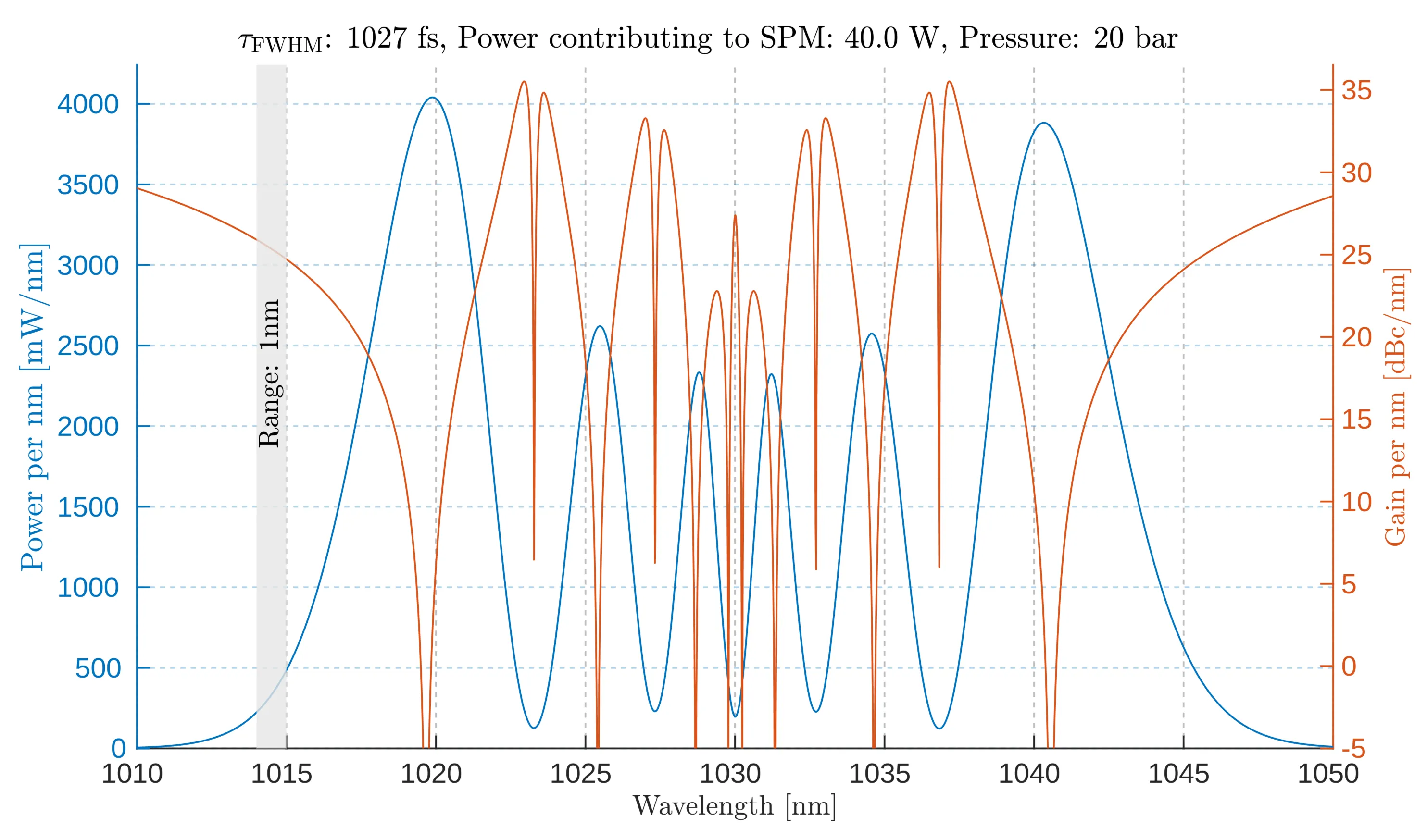

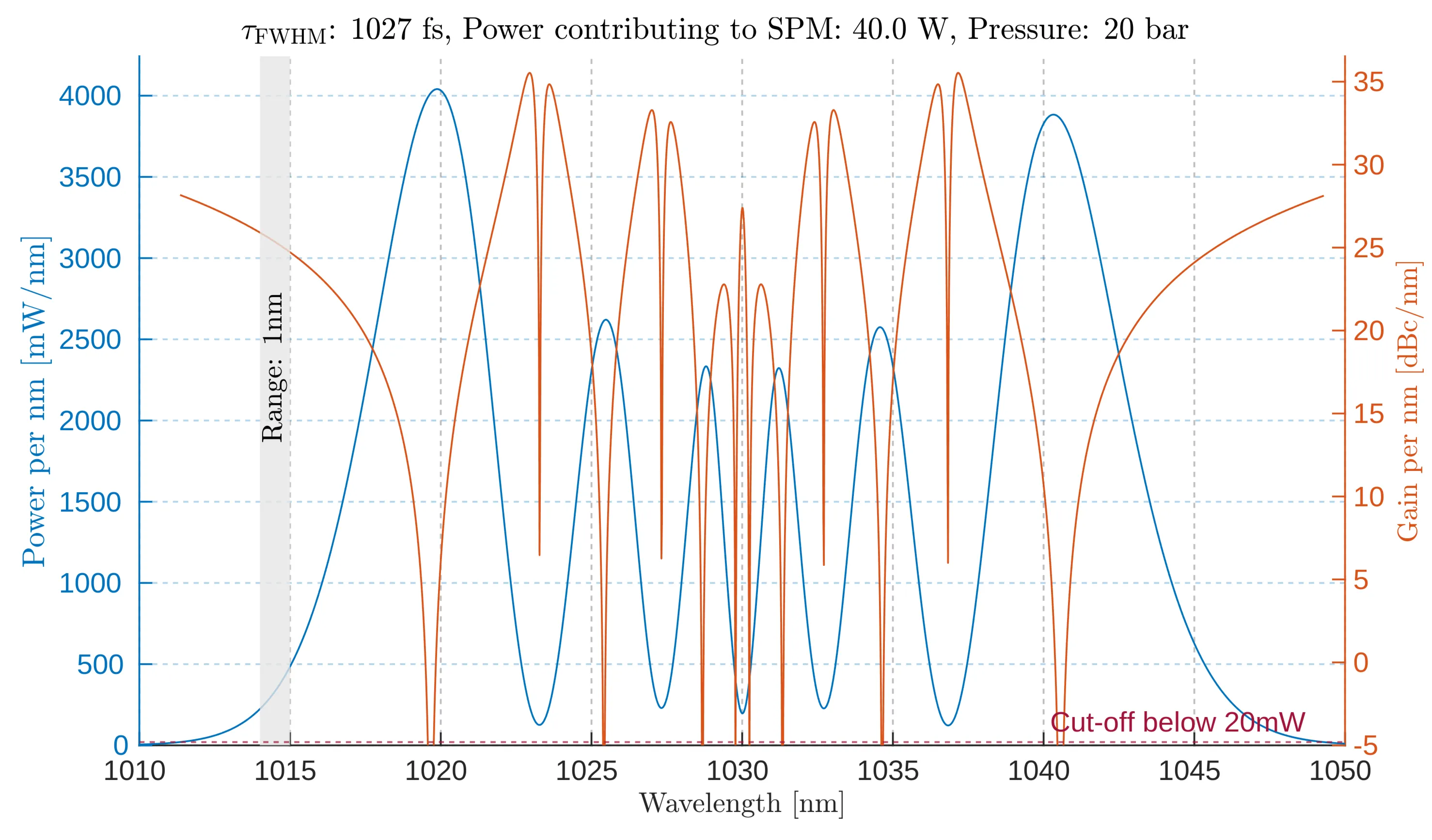

Using this method, we can incorporate fluctuating peak powers and pulse widths into the simulation. Next, we compare the spectra with and without fluctuations. The next figure illustrates this comparison, showing that the ratio between these two spectra can be significant at specific wavelengths, resulting in substantial noise amplification, which we will refer to as noise gain moving forward.

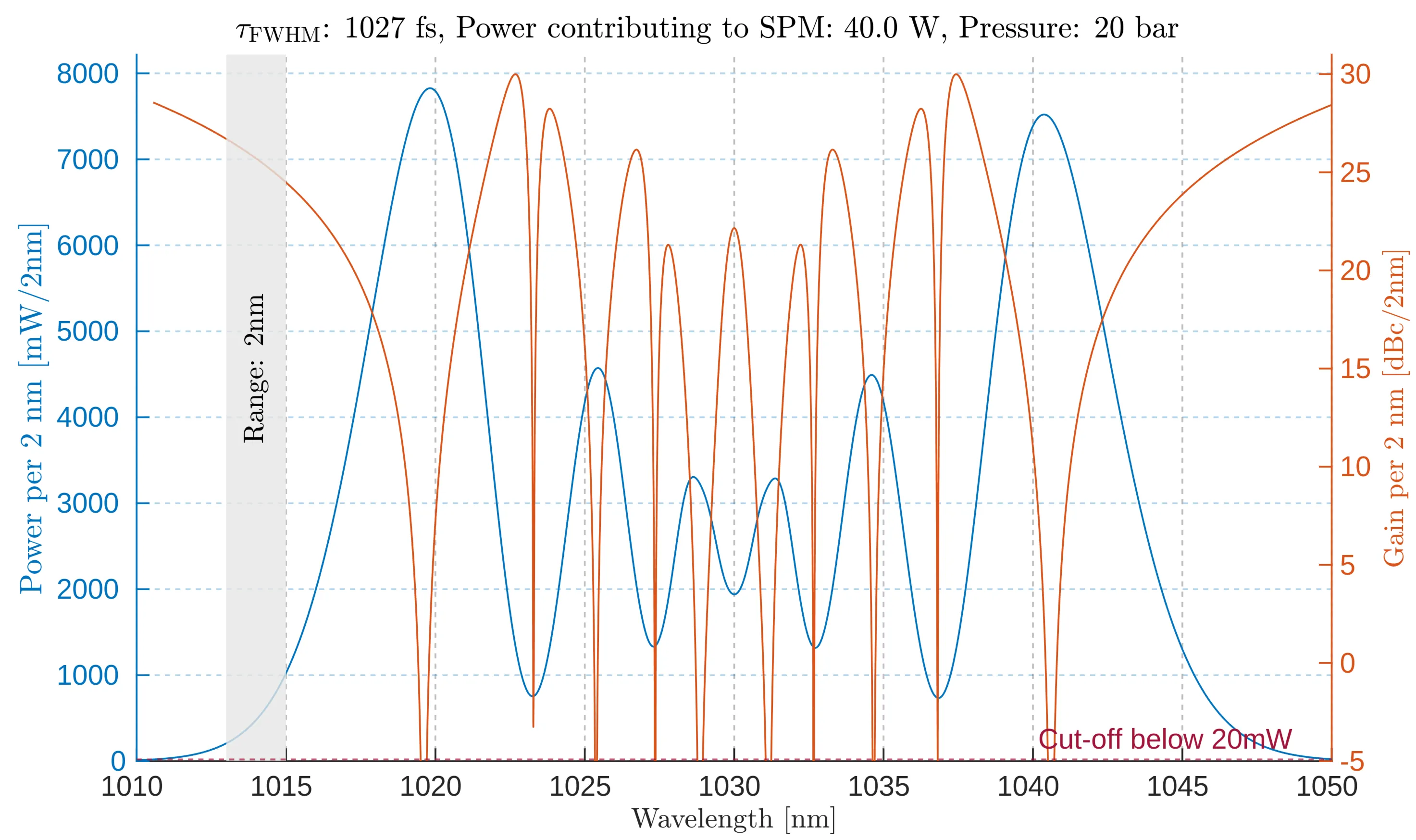

Power density per nanometer (left, blue) and noise gain per nanometer (right, orange) as a function of wavelength. The power density reaches

As the title indicates, "power contributing to SPM" refers to the power that efficiently couples into the fibre. The pulse width for simulation input is determined using the fitted relationship, based on the power coupled into the fibre, considering the presence of an output coupler for the diagnostics beam and an isolator.

It is essential to note that the vertical axes represent gain and power per slice of one nanometer. This is significant because any measurement setup can only capture a finite spectral range. Increasing the slice interval to

Power density per two nanometers (left, blue) and noise gain per two nanometers (right, orange) as a function of wavelength. As expected, the power density reaches

At larger intervals, spectral features become smeared, diminishing the distinct features of spectral broadening. Simulations indicate that a

We observe that at specific wavelengths, the relative change in intensity is significant (on the order of

Power density per nanometer (left, blue) and noise gain per nanometer (right, orange) as a function of wavelength. The power density reaches

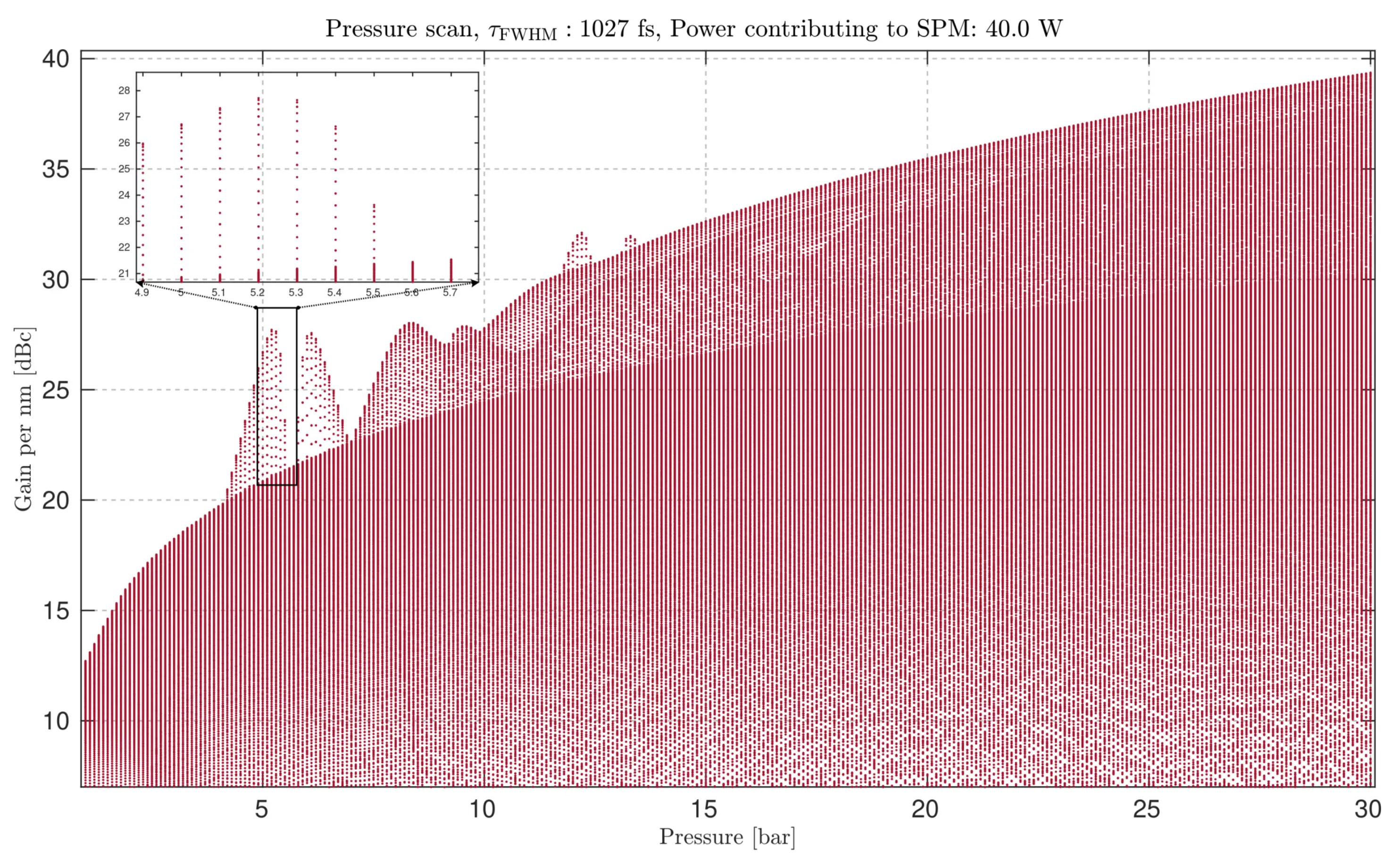

Some high-gain points vanish due to low intensity, which numerical calculations and inherent rounding errors may artificially introduce. For the laser parameters (average power

To illustrate this effect, the next figure presents a pressure scan ranging from

Pressure scan from

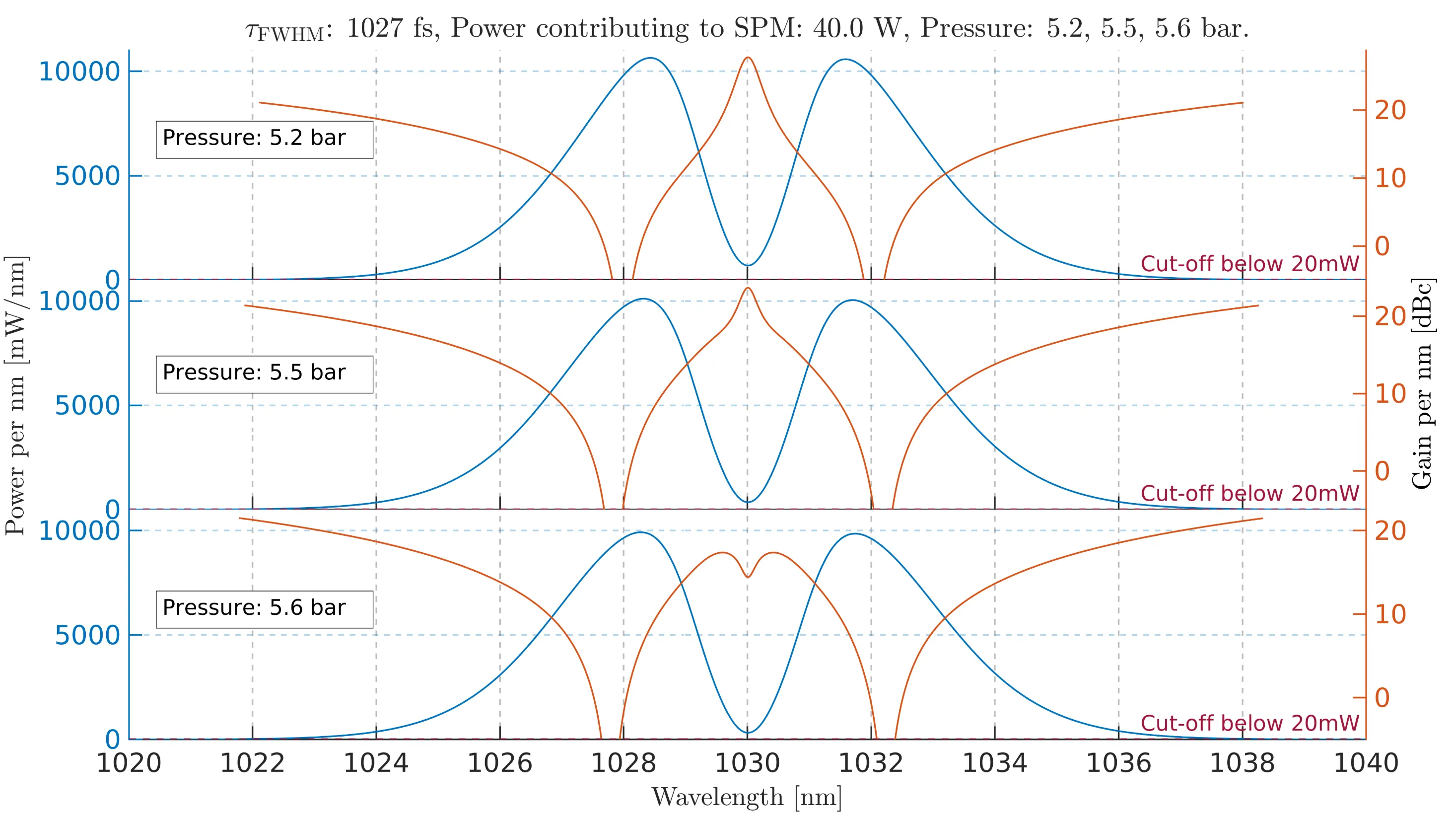

While this outlier may initially appear to be a numerical artefact, the next figure demonstrates that this point is located precisely at the centre of the broadened spectrum:

Power density per nanometer (left, blue) and noise gain per nanometer (right, orange) as a function of wavelength for three different pressures:

Whenever the central peak "splits" into two new peaks, the maximum gain momentarily decreases before these new peaks become dominant, causing the pressure scan to follow a new trend. The noise gains for pressures of

2.7 Using Noise Gain from Spectral Broadening to Infer a Low Shot-Noise Level

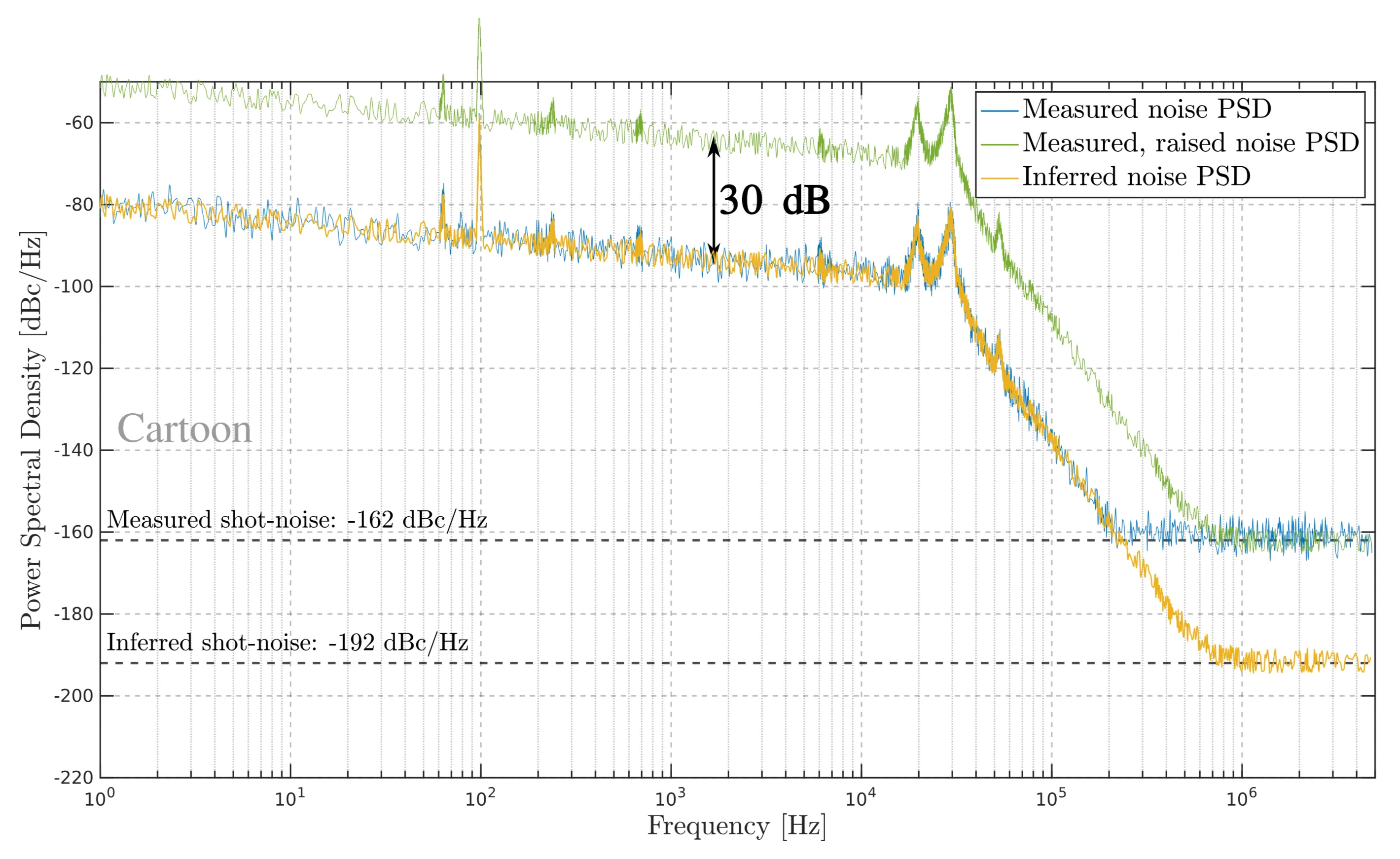

Now that the impact of spectral broadening on noise has been discussed, it is crucial to explain how this technique can be used to infer a low shot-noise level. To illustrate this, the next six figures demonstrate the step-by-step process for estimating a low shot-noise level. The noise trace used in these figures is generated for illustrative purposes.

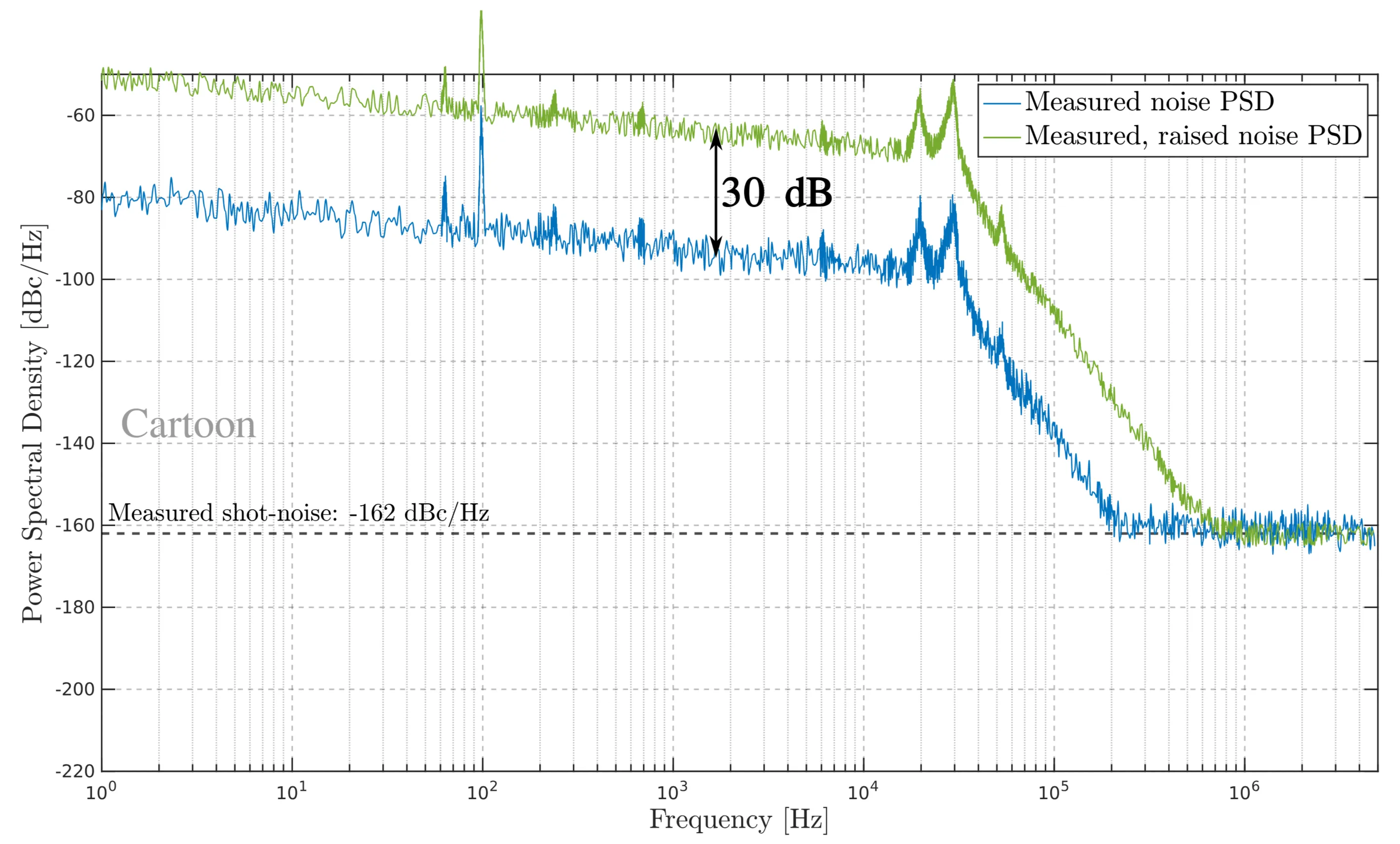

This procedure requires only a single photodiode, a method to raise the noise PSD uniformly across all frequencies, and two measurements: one of the laser before spectral broadening and one after. The strength of this method is that the measurement challenge is shifted from the detection setup to obtaining the uniform noise gain.

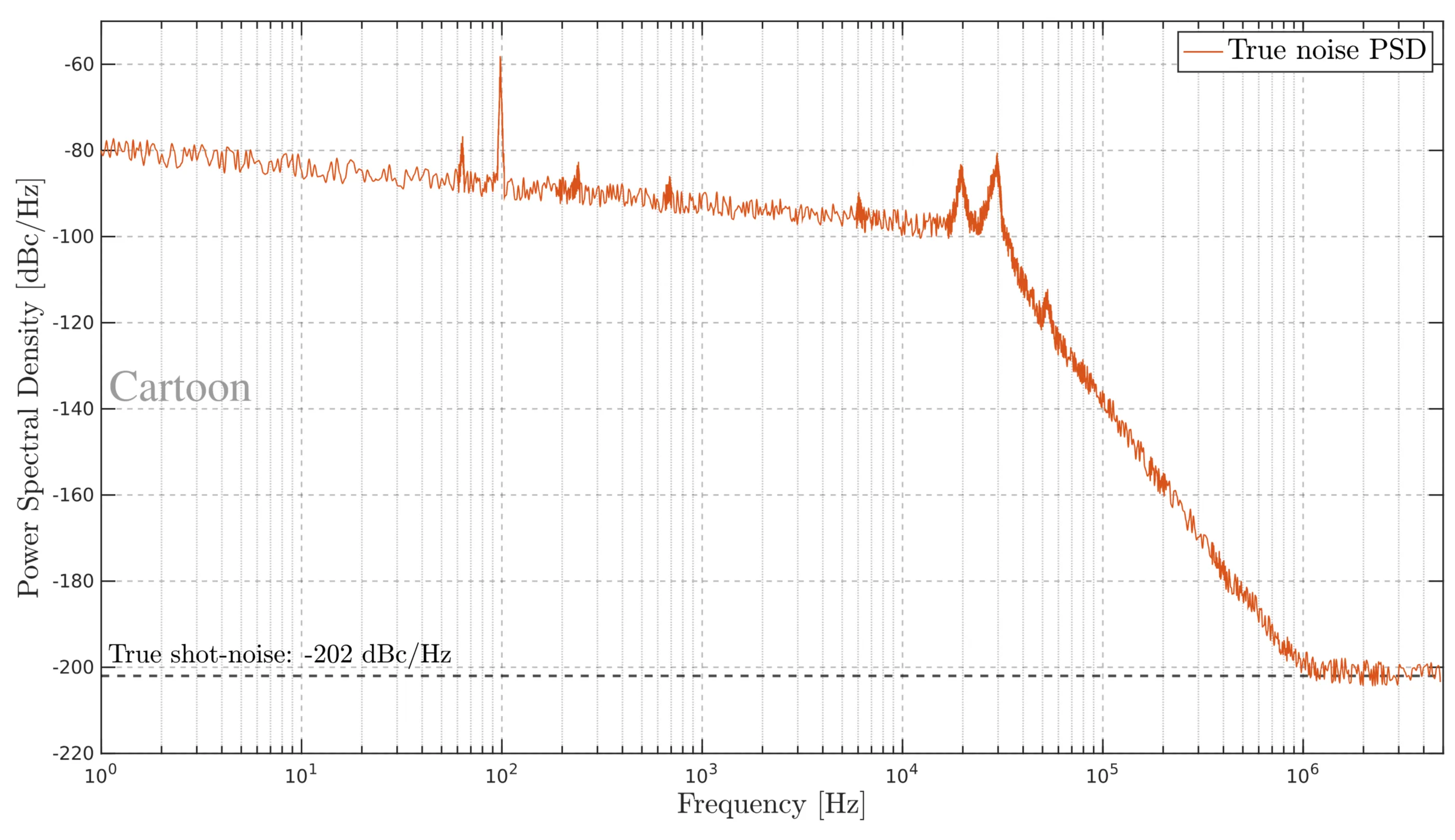

Step 1: Assumed noise PSD of a

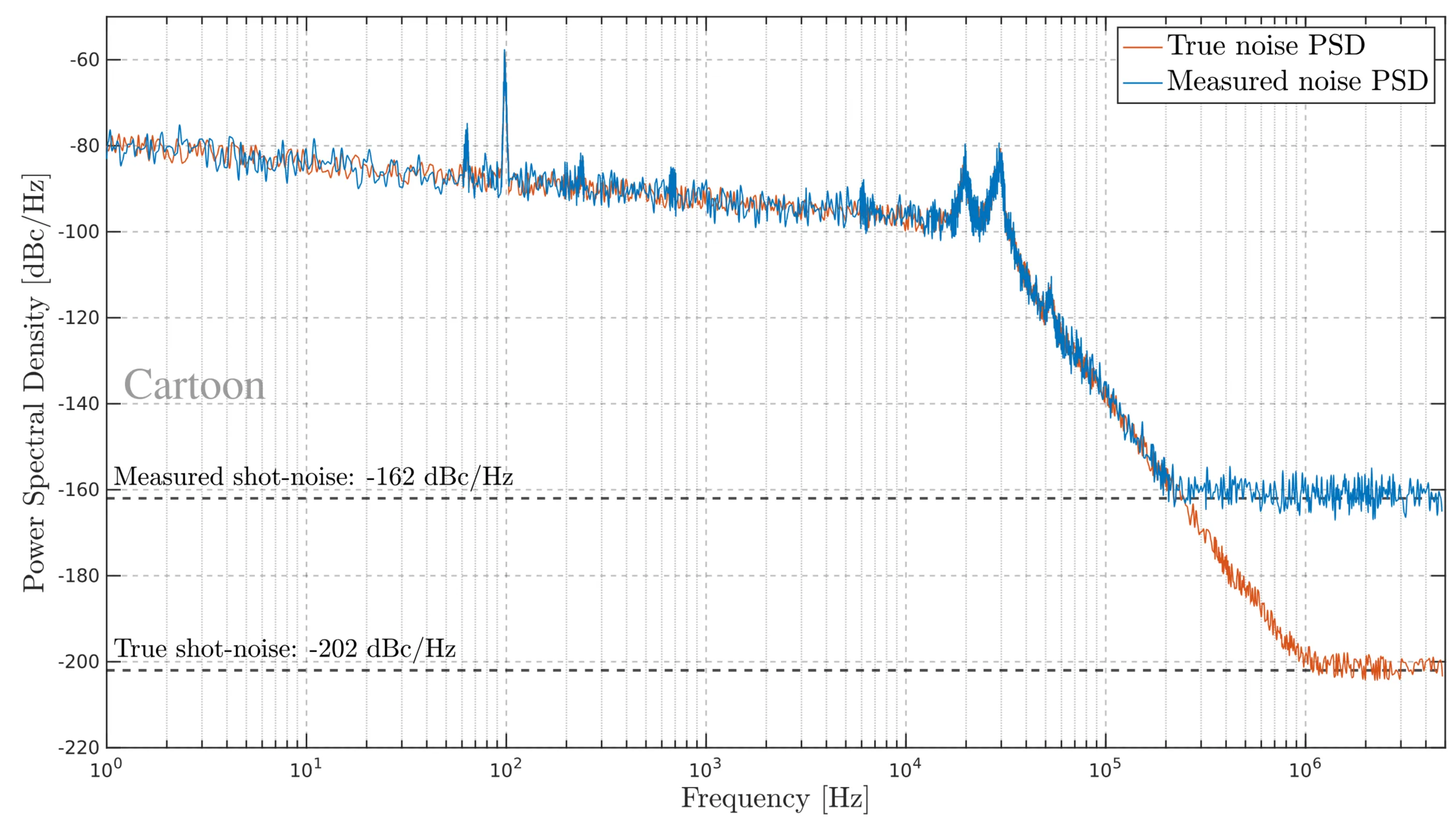

Step 2: Assuming the photodiode can only measure up to

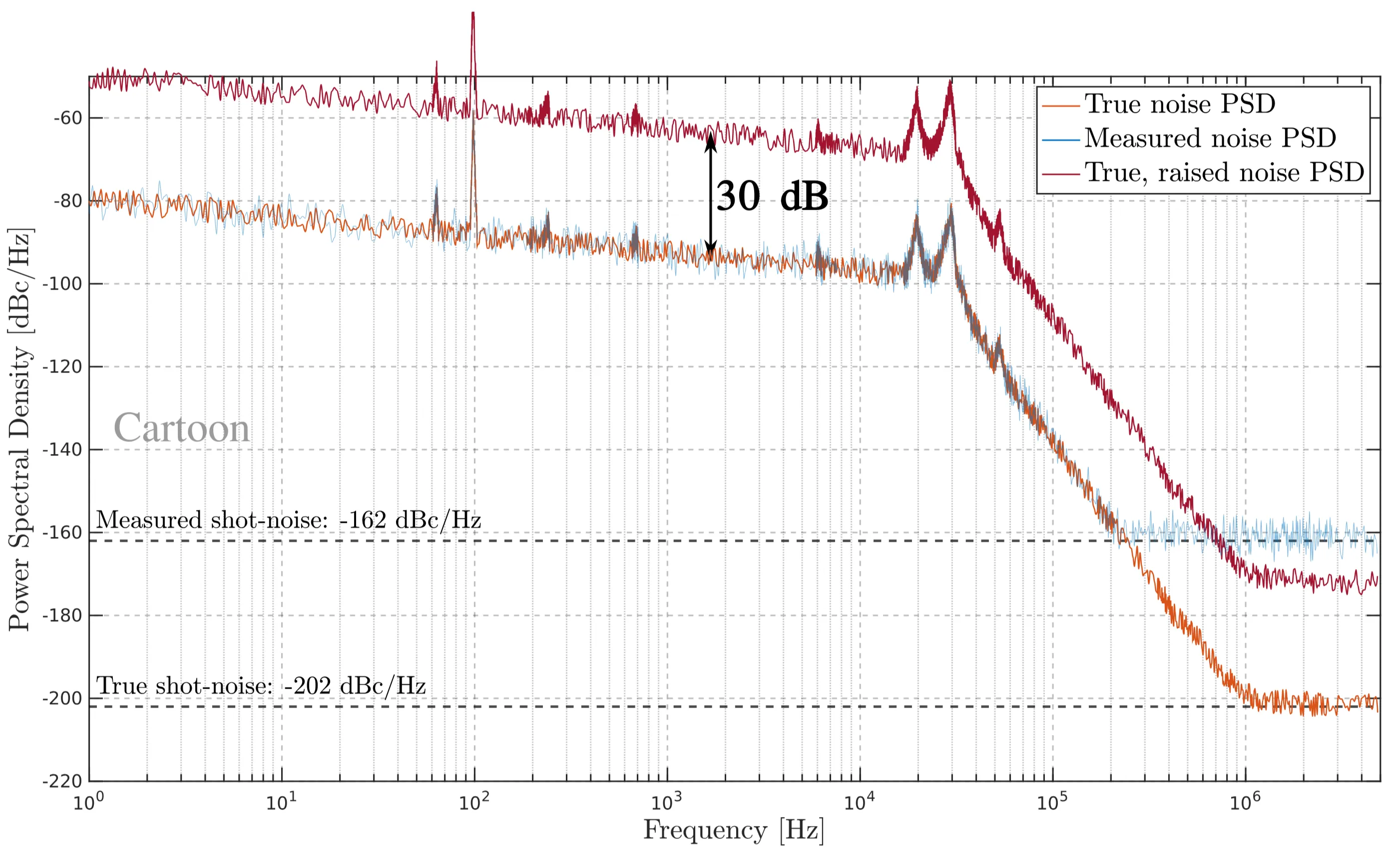

Step 3: Now assume a tool (in this case, spectral broadening) exists that uniformly raises the entire noise PSD by a fixed amount - in this case,

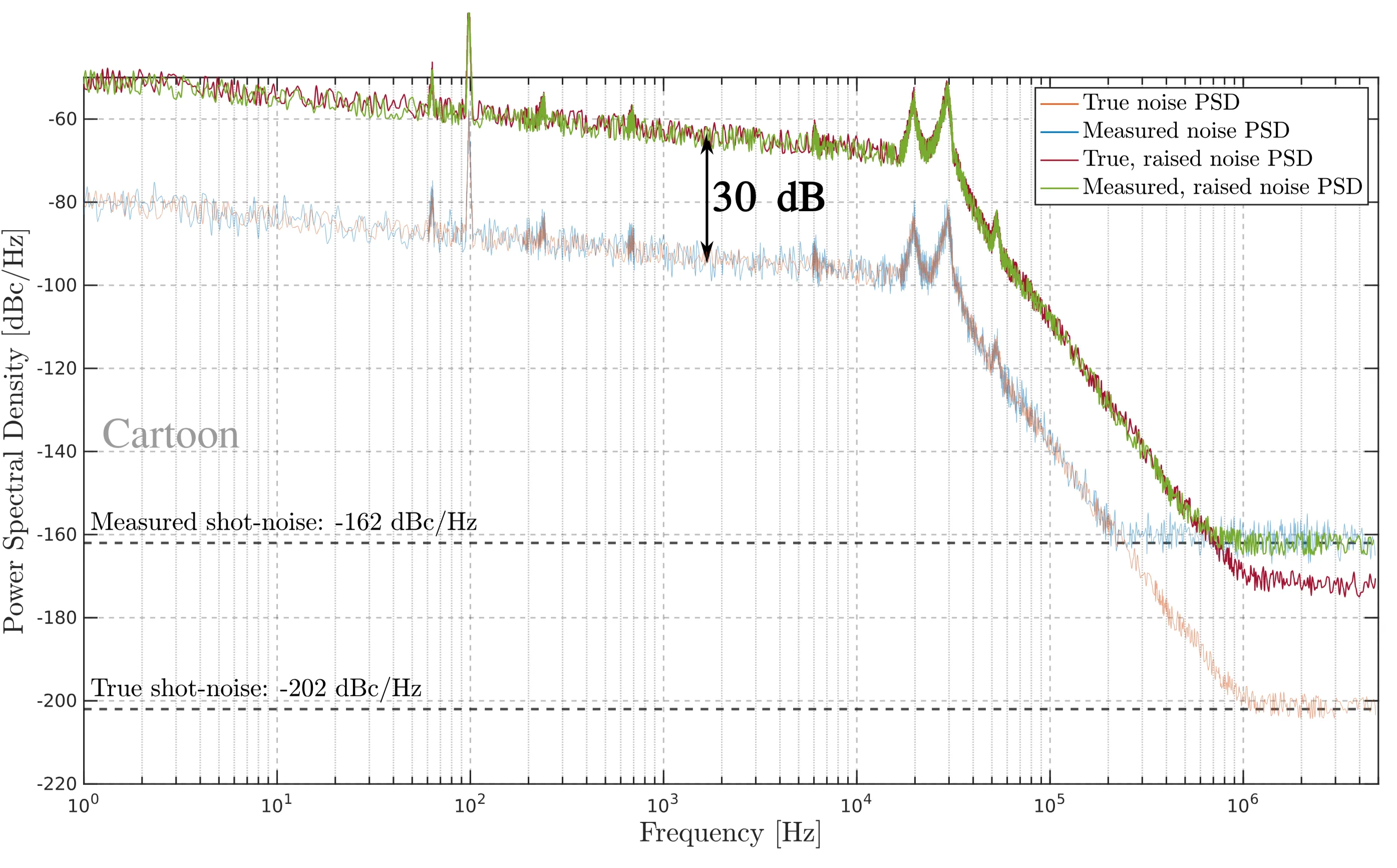

Step 4: Repeating the noise measurement with the laser that has its noise increased, the green curve is obtained in the lab. The measured noise trace will still be limited by the photodiode's shot-noise threshold at

Step 5: After conducting measurements on both the original laser and the noisy laser, the blue and green curves are. They are consistently spaced apart by

Step 6: Given the assumption that the noise gain increases the noise PSD by