Jump back to chapter selection.

Table of Contents

2.1 Attosecond Pulse Trains

2.2 Amplitude Gating

2.3 Polarisation Gating

2.4 Interference Polarisation Gating

2.5 Two-Colour Gating Method

2.6 (Generalised) Double Optical Gating (DOG)

2.7 Ionisation Gating

2.8 Spatial Gating

2.9 Generating Circularly Polarised High Harmonics

2 Generation of Single Attosecond Pulses

High-order harmonics were first observed around 1987 and 1988. However, it took nearly a decade before the first attosecond pulses were reported. In 2001, both the first attosecond pulse train (APT) and the first single attosecond pulse (SAP) were demonstrated. It was already known from theoretical considerations and spectral measurements that high-order harmonics exhibit a flat plateau in their spectra. Furthermore, theoretical models indicated that these harmonics possess nearly constant relative phases. This led to the speculation that the coherent superposition of such harmonics could produce a train of attosecond pulses.

For a long time, the phase relationship between high-order harmonics remained experimentally inaccessible. The emergence of attosecond science, and particularly the generation and measurement of attosecond pulses, became possible only after reliable experimental techniques, such as RABBITT (Reconstruction of Attosecond Beating By Interference of Two-photon Transitions) and attosecond streaking, were developed to determine these phases.

Although each burst in an APT has a sub-femtosecond duration, the overall pulse train typically spans several tens of femtoseconds, mirroring the envelope of the driving laser pulse. For many applications requiring sub-femtosecond temporal resolution to probe ultrafast electron dynamics, single attosecond pulses are necessary. In the following sections, we will discuss the most common gating techniques employed to isolate or generate SAPs.

2.1 Attosecond Pulse Trains

The harmonic spectrum produced during high-order harmonic generation (HHG) consists of a series of narrow peaks. When a multi-cycle (long) driving laser pulse is used, and the generation medium possesses inversion symmetry (like noble gas atoms), only odd harmonics of the fundamental laser frequency

Consider the superposition of different odd harmonics. If we represent the spectral amplitude of the

In the simplest case, if the spectral phase is linear with frequency, meaning

This expression describes an attosecond pulse train (APT): a series of short bursts of radiation separated in time by

It is important to note that a TL attosecond burst does not require all harmonic components to have the same absolute phase (

Interestingly, the regular pulsed structure of

Due to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, it is impossible to define an "instant" of emission precisely associated with a specific XUV frequency

For discrete harmonics, this can be approximated by the phase difference between adjacent harmonics:

which applies to harmonics centred around the frequency

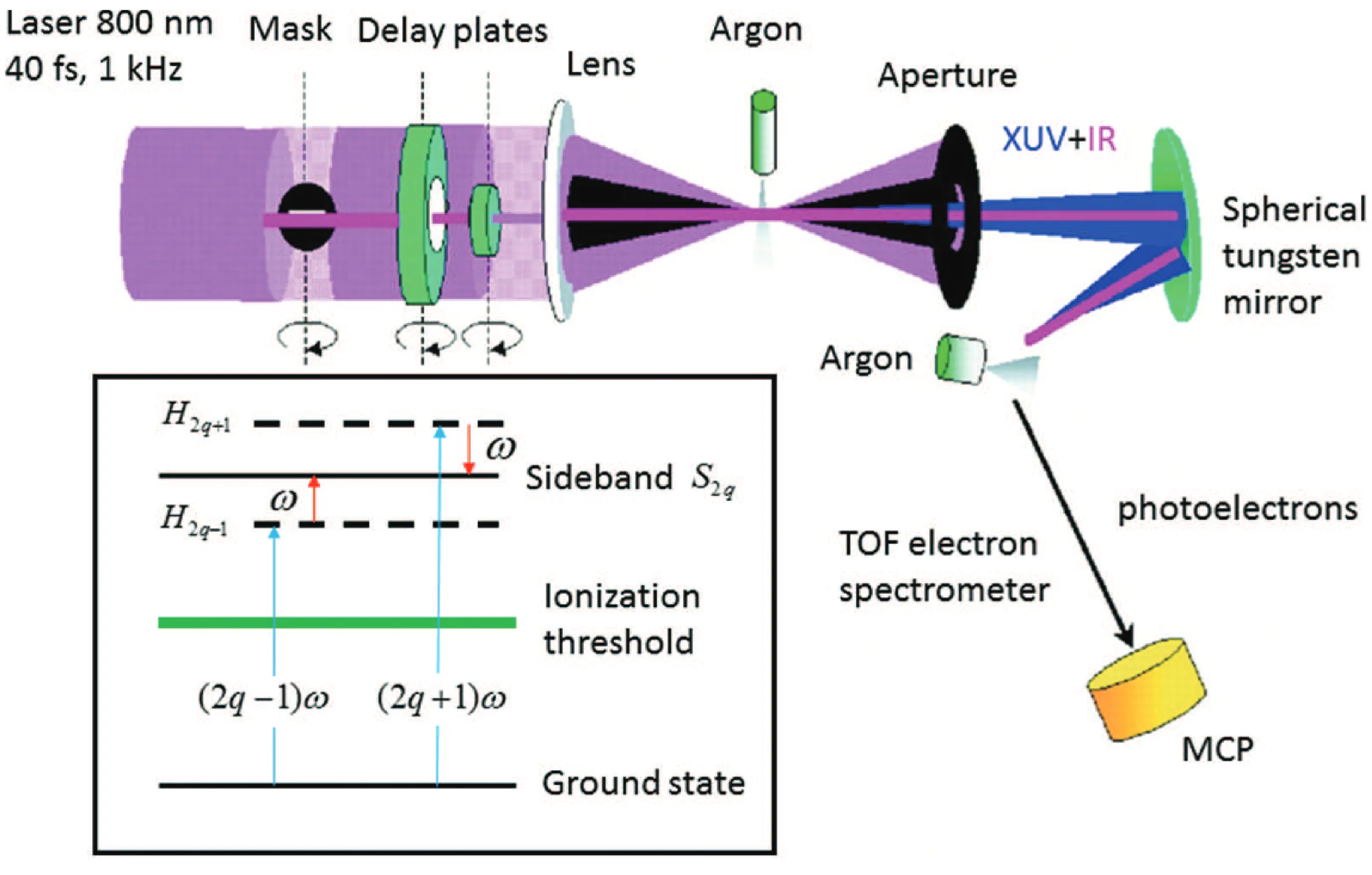

Consider a typical experimental setup used for the generation and characterisation of attosecond pulse trains:

In this setup:

- High-order harmonics are generated by focusing an intense femtosecond laser pulse into a gas target (such as argon).

- An aperture may be used to block the highly divergent part of the fundamental IR beam, allowing the generated XUV harmonics (which are often more collimated) and a portion of the IR beam to co-propagate along the same axis.

- A suitable mirror (like a holey mirror or a spatially separated dual mirror) deflects or transmits the combined beam into a secondary gas target (often the same gas species) within a spectrometer. Here, the XUV photons ionise the target atoms, generating photoelectrons.

- The kinetic energy spectra of these photoelectrons are measured, typically as a function of the time delay between the IR pulse and the XUV APT, which is controlled by an optical delay line. The IR field acts as a "streaking" or "modulating" field for the photoemission process.

The two-dimensional electron spectra (energy versus delay) obtained from these measurements are known as spectrograms or streaking traces (or RABBITT traces if specific sidebands are analysed). These traces contain encoded information about the spectral amplitudes and phases of the harmonics, allowing for the reconstruction of the temporal structure of the attosecond pulses in the train.

2.2 Amplitude Gating

In high-order harmonic generation driven by a multi-cycle laser pulse, discrete harmonics arise from the coherent superposition of XUV bursts generated with a periodicity of

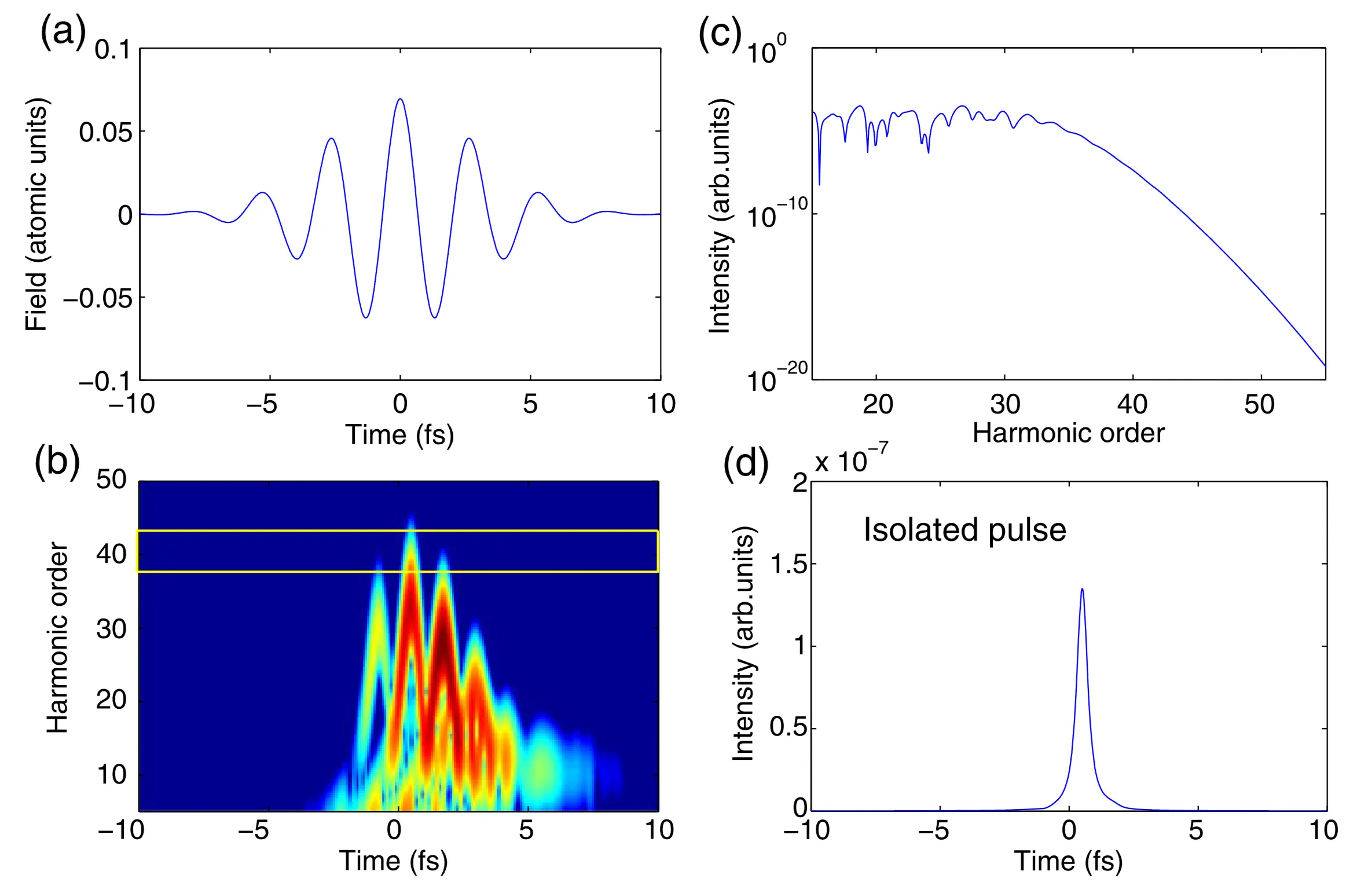

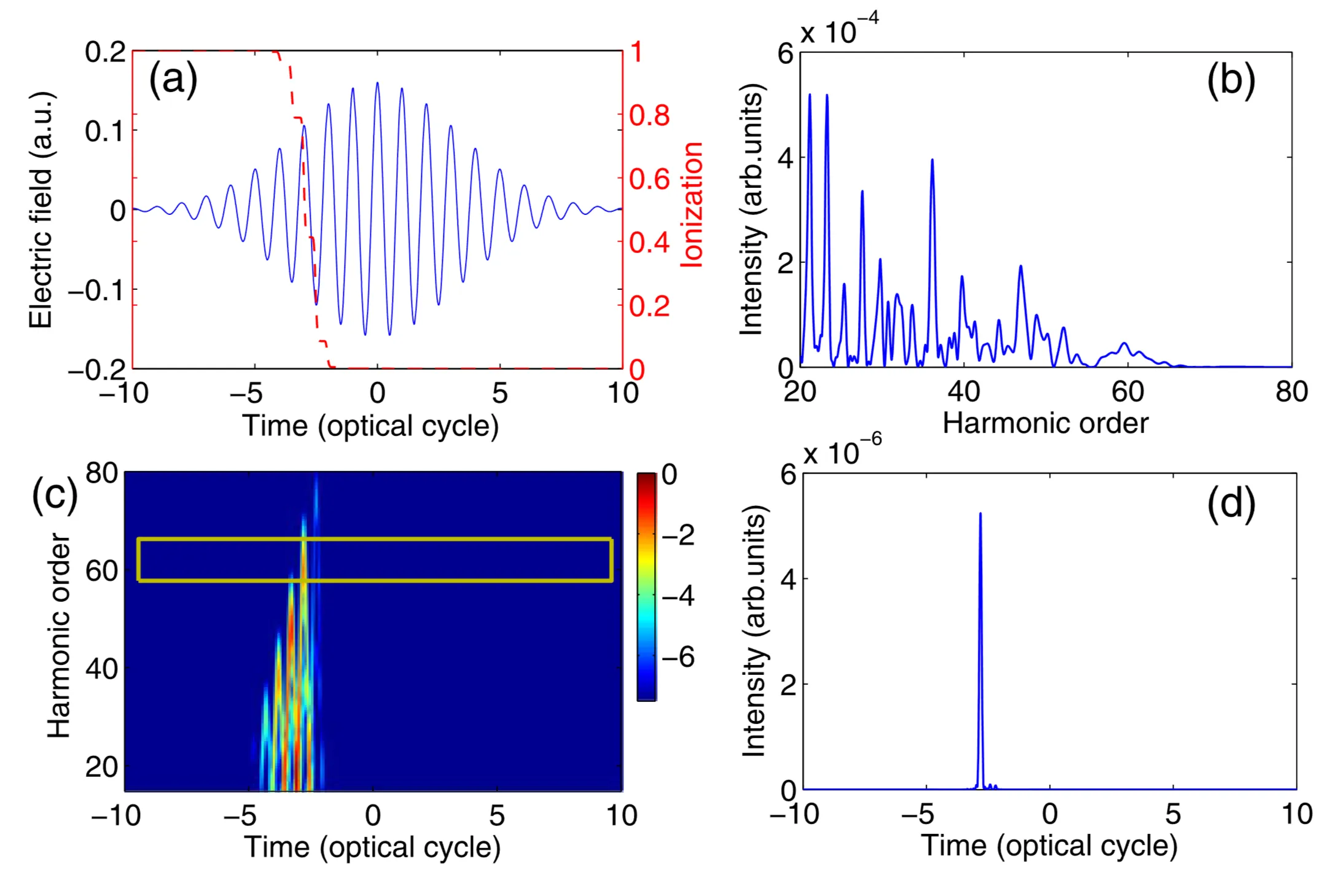

For this method to be effective, ultrashort driving laser pulses (typically few-cycle, duration

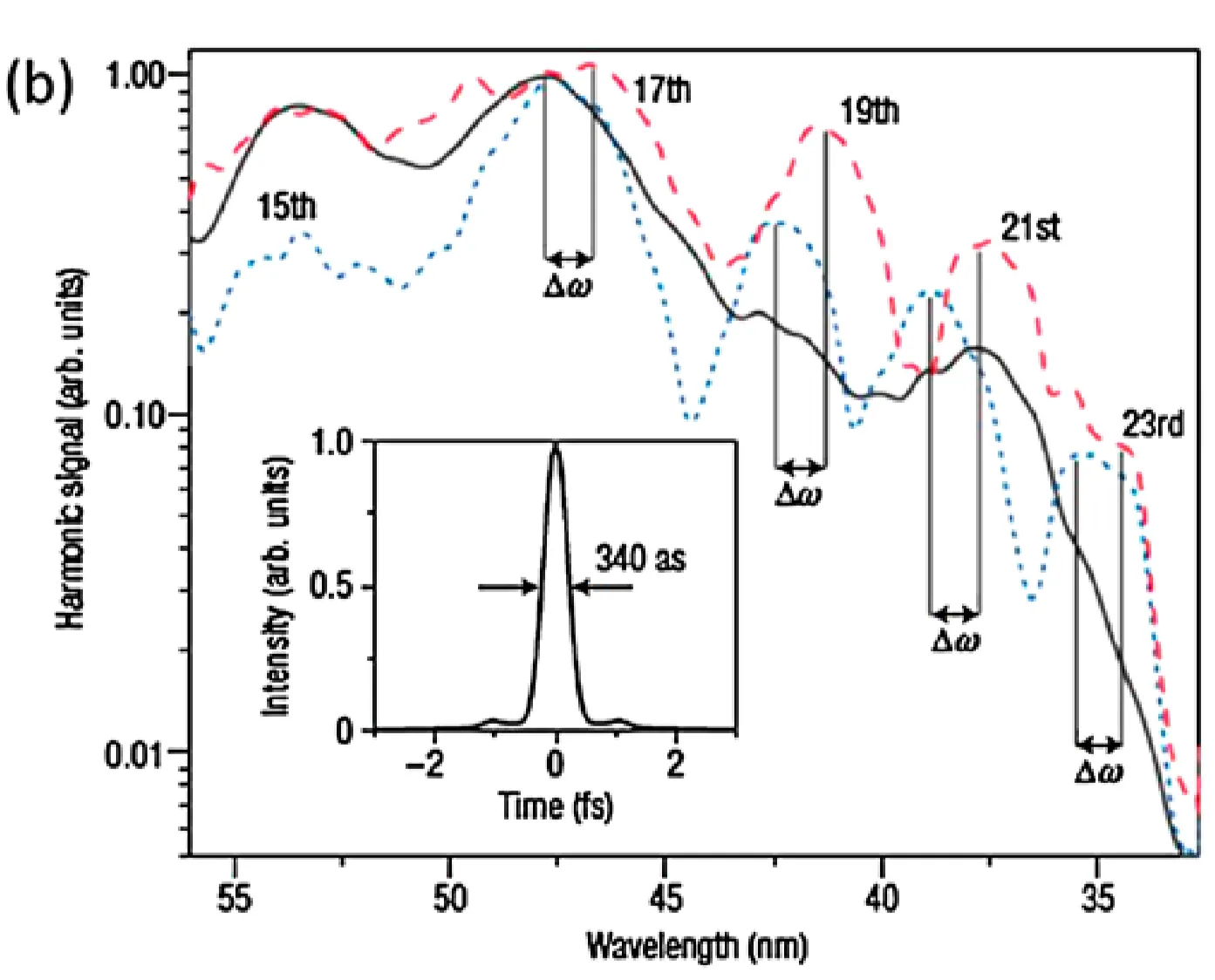

When the driving pulse consists of only a few optical cycles, the highest photon energies—those near the cutoff region—are predominantly generated during the single half-cycle of the electric field that has the highest peak amplitude. This is illustrated in figure (b) below. This confinement results in a continuous harmonic spectrum in the cutoff region, as shown in (c). By spectrally selecting only these cutoff components from the high-harmonic beam (using appropriate XUV filters or mirrors), an isolated light pulse with an attosecond temporal duration can be obtained, as depicted in (d).

The electric field of the driving laser pulse can be described as:

where

2.3 Polarisation Gating

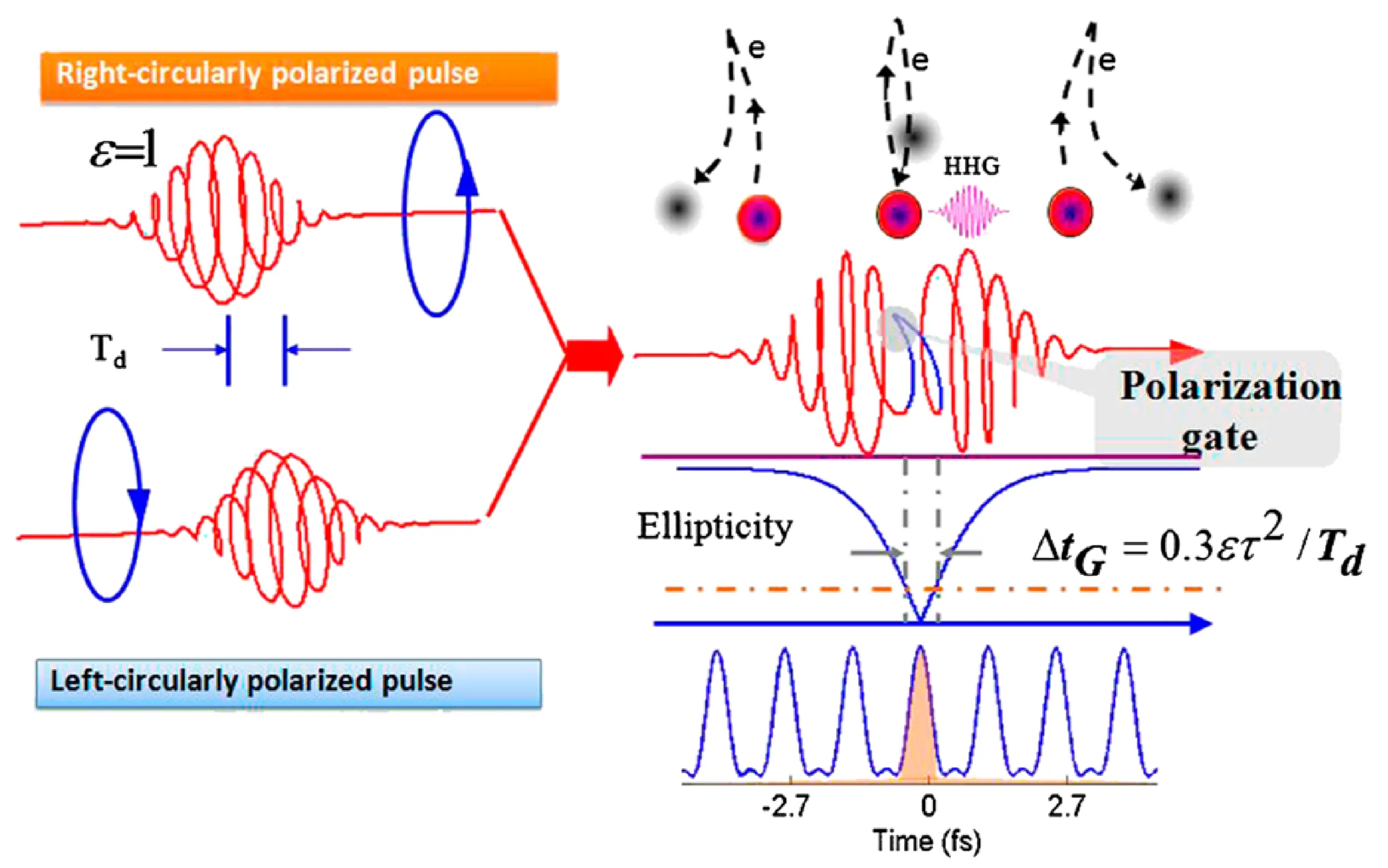

Polarisation gating (PG) is a technique that uses the strong dependence of HHG efficiency on the ellipticity of the driving laser field to create a short temporal window for harmonic generation. The method typically involves synthesising a driving laser field whose polarisation state changes rapidly with time. One common approach is to combine a right-circularly polarised pulse with a time-delayed left-circularly polarised pulse of similar characteristics. This creates a composite laser field which is elliptically (or circularly) polarised at the leading and trailing edges of the pulse superposition, but becomes transiently linearly polarised around the point of temporal overlap (pulse centre).

Since HHG efficiency is very high for linearly polarised light but is strongly suppressed for elliptically or circularly polarised light (because the electron trajectory is less likely to return to the parent ion), efficient harmonic generation is confined to the short time interval when the field is predominantly linear.

The polarisation gate width (

where

A limiting factor for PG (and other gating methods) can be the ionisation of the target medium. If the leading parts of the gate (where polarisation might still be somewhat elliptical but intensity is rising) cause significant ionisation, the neutral atom density available for HHG in the linearly polarised part of the gate is depleted, reducing efficiency. For example, if the pulse duration exceeds a certain value (

A PG field with time-dependent ellipticity can be generated experimentally by passing an initially linearly polarised femtosecond pulse through a setup involving birefringent optics. For instance, a first birefringent plate (like a thick quartz plate or a split pair of calcite wedges) can split the pulse into two orthogonally polarised components, introducing a controllable time delay

HHG efficiency is highly sensitive to ellipticity because, in an elliptically polarised field, the ionised electron acquires a significant transverse momentum component. This causes a lateral drift away from the parent ion, reducing the probability of recollision and thus suppressing harmonic emission. Therefore, efficient HHG requires a polarisation gate where the ellipticity remains very low (close to linear polarisation) for at least one optical half-cycle.

The duration

The PG window (for instance, defined as the period during which ellipticity is below

2.4 Interference Polarisation Gating

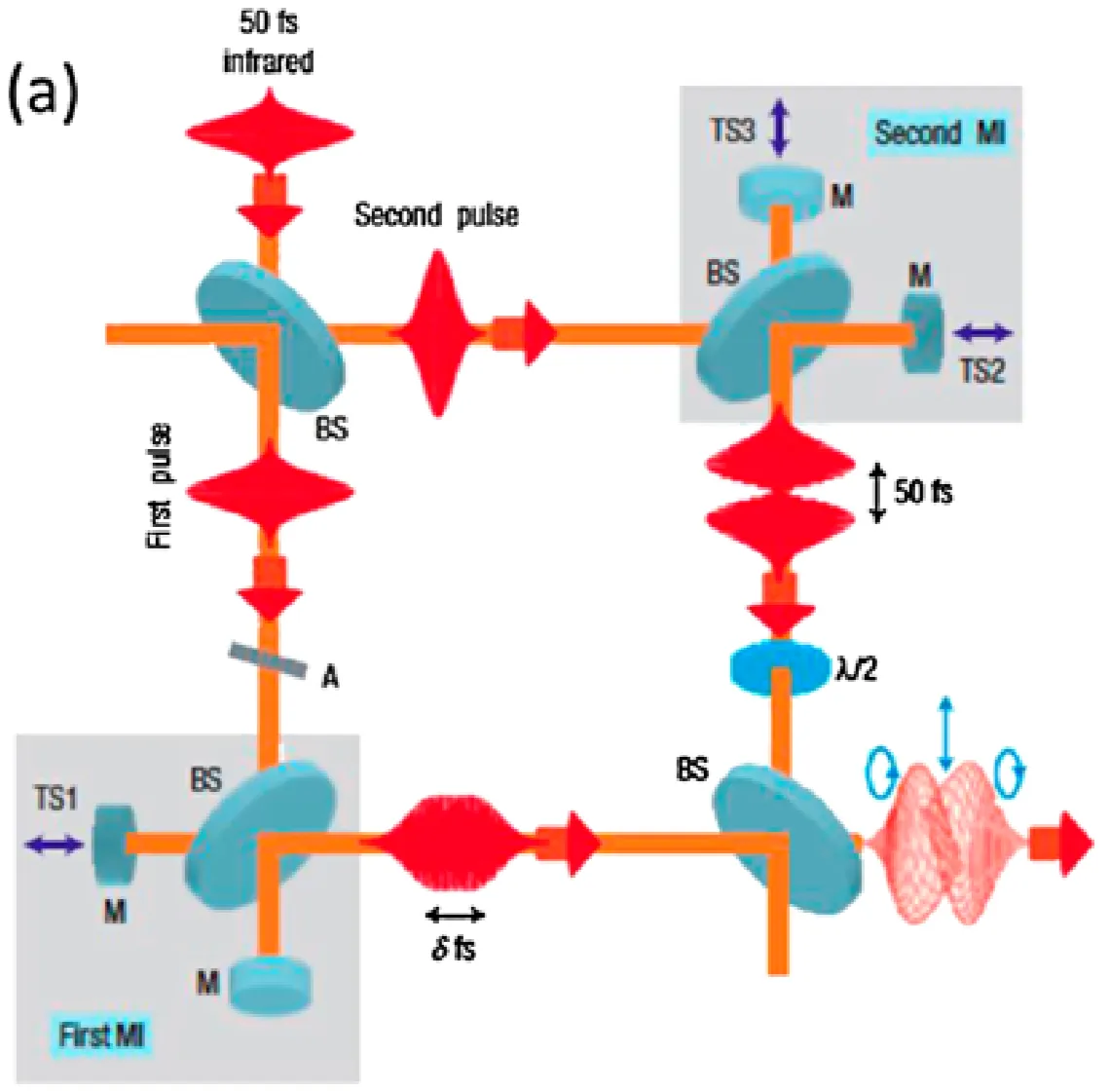

Interference Polarisation Gating (IPG), sometimes also related to "generalised polarisation gating", is a more complex but potentially more efficient or flexible variation of the standard polarisation gating technique. The following figure illustrates a conceptual setup, which can involve a double Michelson-type interferometer or cascaded birefringent elements:

In a typical IPG scheme based on interferometry:

- An initial linearly polarised pulse is split into two or more replicas.

- These replicas traverse different optical paths, where their polarisation states and relative delays are precisely controlled. For instance, one path might create a strong linearly polarised central pulse, while another path creates orthogonally polarised, time-delayed "pedestal" pulses.

- When these beams are recombined collinearly, the interference results in a synthesised pulse that is linearly polarised only at its very centre, while being elliptically or circularly polarised in the leading and trailing wings. This creates a very sharp and effective polarisation gate.

Although IPG techniques can be more demanding in terms of alignment and stability of the interferometric paths, they can offer greater flexibility in tailoring the temporal profile of the gate and potentially allow the use of somewhat longer driving pulses compared to basic PG, while still achieving a very short gating window.

A limitation common to many gating techniques, including IPG, is its sensitivity to the CEP of the driving pulse, especially when using few-cycle pulses. As shown in the figure below, the generated supercontinuum (indicative of SAP generation) can depend strongly on CEP stability. Therefore, CEP-stabilised driving pulses are often essential for producing consistent and isolated attosecond pulses with IPG.

2.5 Two-Colour Gating Method

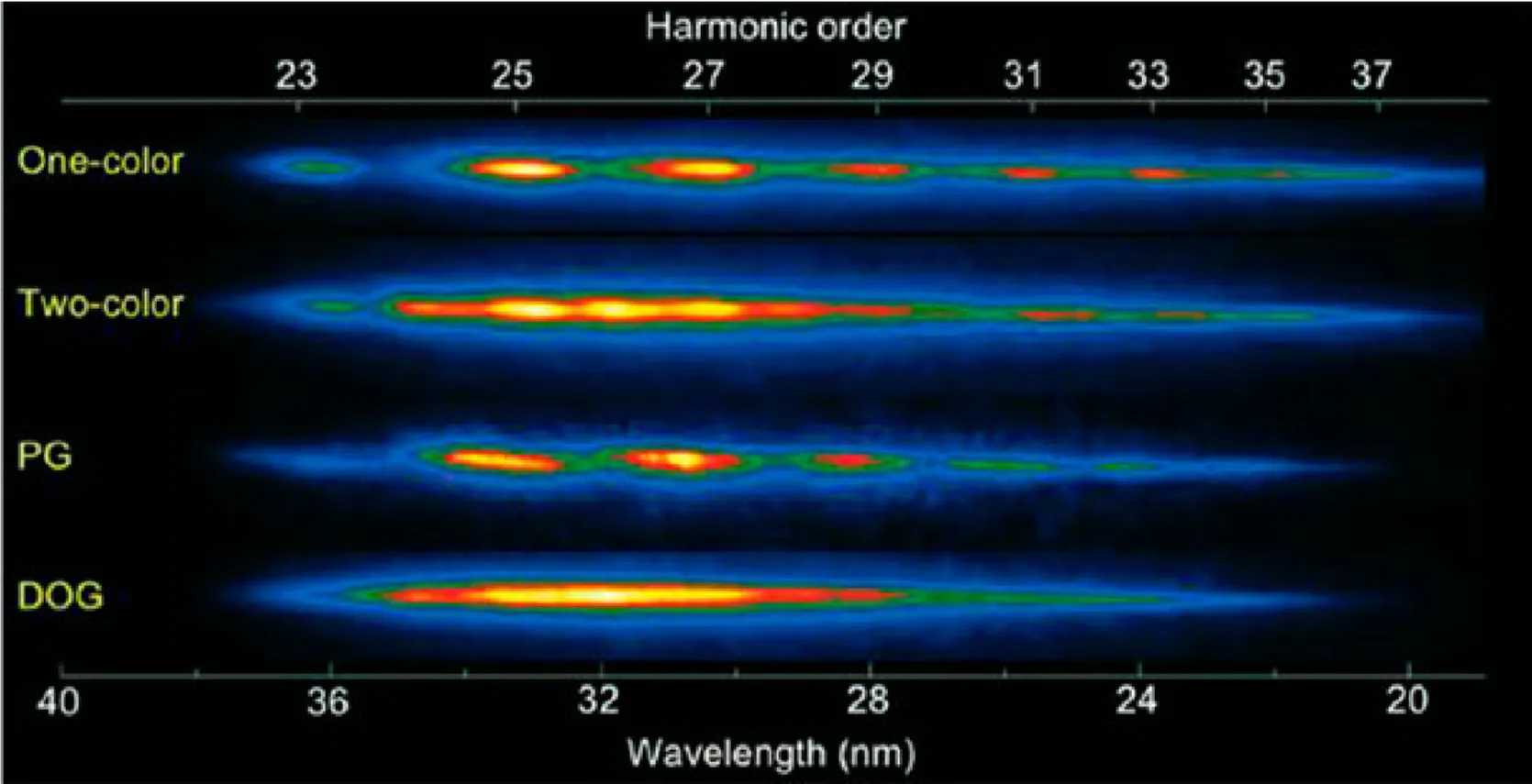

To relax the stringent requirement for ultrashort (few-cycle) driving pulses inherent in some gating techniques, the temporal symmetry of the HHG process can be broken by introducing a second, weaker laser field at a different frequency, typically the second harmonic (

At the same total pulse energy, this method can sometimes enhance overall HHG efficiency for certain harmonic ranges or reduce ionisation at the leading edge of the driving pulse compared to a single-colour pulse of the same peak intensity, allowing for the use of driving pulses with durations up to, for instance,

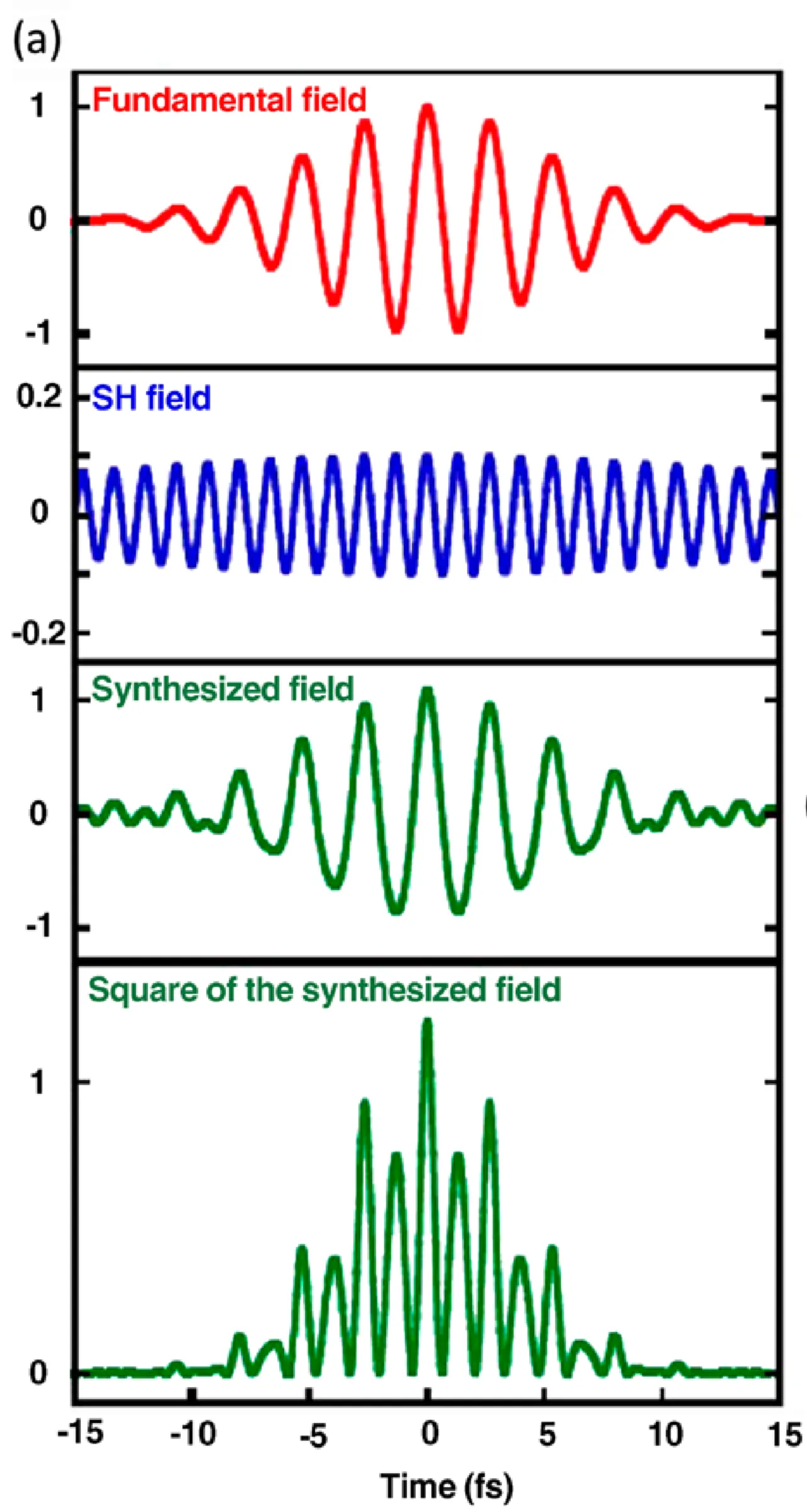

Consider the synthesised electric field from the combination of a fundamental frequency (

where

As shown, by carefully choosing the relative phase and intensity (for instance, using a weaker second harmonic where

2.6 (Generalised) Double Optical Gating (DOG)

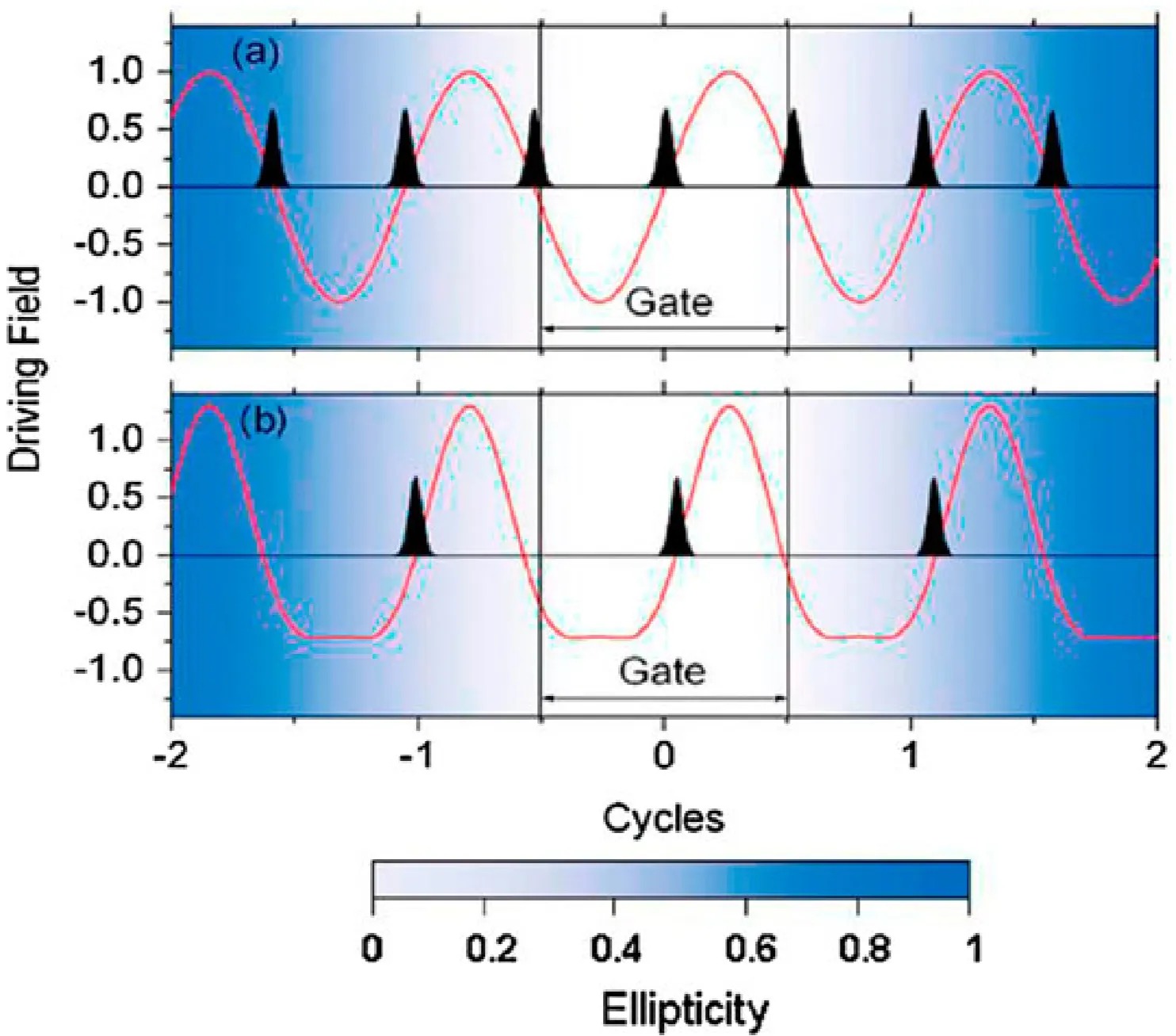

Combining a fundamental laser field with its second harmonic (a two-colour field as discussed in section 2.5) inherently breaks the inversion symmetry of the total driving field waveform,

The Double Optical Gating (DOG) technique often refers to combining such a two-colour gating approach with polarisation gating. By using a two-colour field where the components also have specific, controlled polarisation states (for instance, the fundamental and second harmonic are orthogonally polarised, or both are used to create a time-dependent ellipticity similar to PG but with the added asymmetry of the two-colour field), a very effective temporal gate can be created.

The figure compares standard polarisation gating (PG) with DOG. Unlike conventional PG which might require very short pulses for a narrow linear gate, DOG can offer advantages. For instance, it can allow the generation of single attosecond pulses (SAPs) even when the effective gate width created by the polarisation control is wider than

Generalised DOG (GDOG) might involve more complex multi-colour fields or polarisation shaping to further optimise the gating.

2.7 Ionisation Gating

Ionisation gating relies on the intrinsic dynamics of the HHG process itself, particularly the strong dependence of HHG efficiency on the availability of neutral atoms and the ionisation rate. When atoms are exposed to an intense laser field whose peak intensity is sufficient to cause significant or even complete ionisation (an "over-saturated" field), rapid ionisation can occur within a single optical cycle or less. If the neutral target is completely depleted at the leading edge of the pulse, subsequent parts of the pulse cannot generate harmonics.

- Leading Edge: Rapid ionisation occurs. Harmonics are generated during this phase, but as the neutral atom population depletes, HHG efficiency drops.

- Trailing Edge: No significant HHG occurs due to the absence of neutral atoms, which are required for the first step (ionisation) of the three-step model.

Thus, HHG is effectively confined to the leading edge of the pulse, creating an "ionisation gate" even with multi-cycle driving pulses. The temporal window for HHG is determined by how quickly the medium ionises.

Moreover, as the laser intensity increases rapidly at the leading edge of a very intense pulse, each subsequent half-cycle that encounters neutral atoms reaches a higher peak intensity. This means that progressively higher-order harmonics, extending further into the cutoff, are generated by these successive half-cycles on the rising edge. Once the intensity is high enough to fully ionise the medium, HHG ceases. The highest-order harmonics, forming a continuous spectrum near the overall cutoff, are generated by the last few half-cycles before complete depletion. For instance, harmonics might be suppressed after

By spectrally filtering out the lower-order, discrete harmonics (which might be generated over several half-cycles before complete depletion), a single attosecond pulse (SAP) originating from the continuous spectrum generated at the very leading edge of the pulse can be isolated. Ionisation gating is particularly effective because it utilises the strong-field ionisation dynamics to confine HHG to a narrow temporal window, potentially enabling the generation of isolated attosecond pulses without necessarily requiring extremely short few-cycle driving pulses, provided the intensity rises sharply enough to deplete the medium quickly.

2.8 Spatial Gating

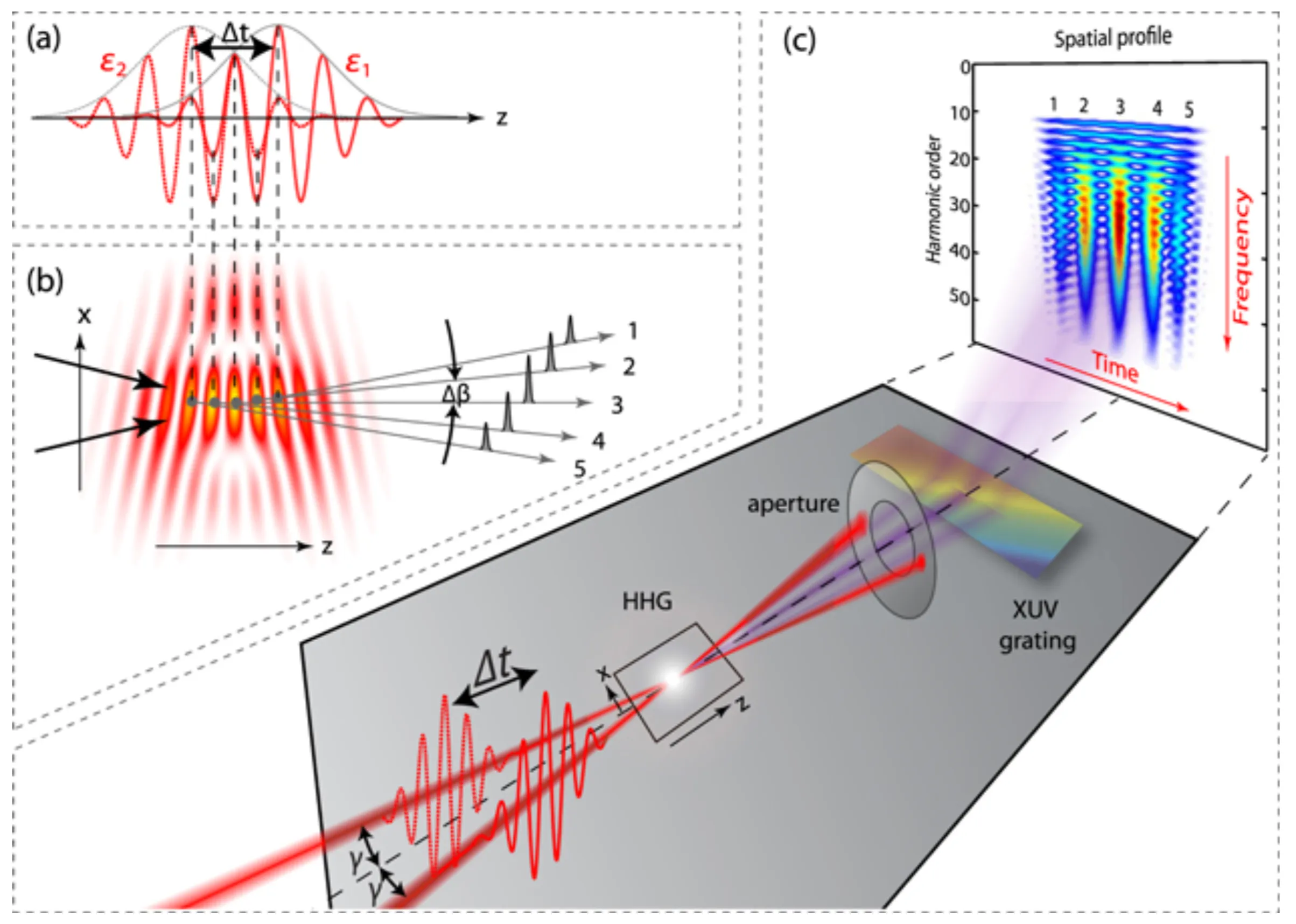

The key idea behind spatial gating is to spatially separate single attosecond pulses (SAPs) that are generated during different half-cycles (or full cycles, depending on the scheme) of the driving laser field. This is achieved by arranging the HHG process such that each successively generated attosecond burst is emitted in a slightly different direction.

One method to implement this is by introducing a controlled tilt in the phase front of the generating infrared (IR) pulse relative to its intensity front. This is often called inducing a pulse-front tilt (PFT). This can be achieved, for instance, by passing the IR beam through a pair of wedged glass prisms before focusing it into the gas target. With such a tilt, the peak of the laser field arrives at different transverse positions in the focus at slightly different times. Consequently, each attosecond burst generated within what would otherwise be an APT is emitted from a slightly different transverse position or, more importantly, in a slightly different propagation direction.

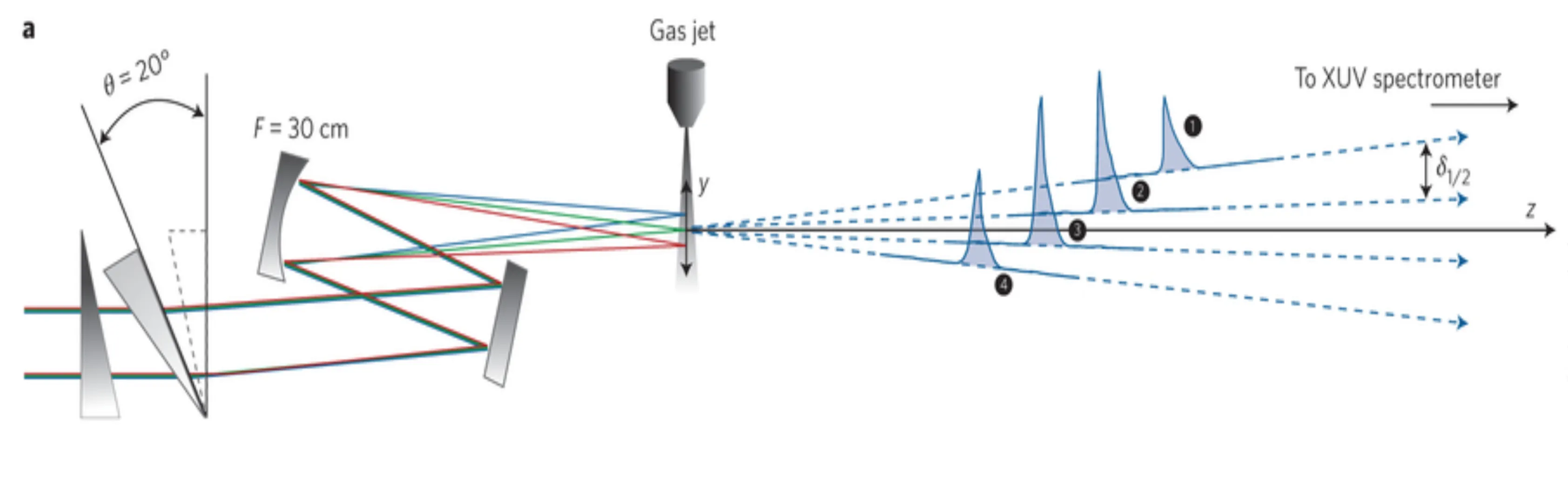

If the wavefront rotation (angular sweep) within one half-cycle (or full cycle) of the driving laser is larger than the intrinsic divergence angle of the individual attosecond pulses, each burst can be spatially separated in the far field. This allows for the selection of a single attosecond pulse from the train using a spatial filter (like an aperture). However, this method typically still requires relatively short driving pulses, for instance, below

One well-known configuration for spatial gating based on PFT is the Attosecond Lighthouse setup:

In the Attosecond Lighthouse, the pulse-front tilt effectively "sweeps" the direction of harmonic emission over time, causing each attosecond burst to be emitted at a distinct angle, analogous to the beam from a lighthouse.

Alternatively, spatial gating can be implemented using non-collinear optical gating, where two (or more) driving laser pulses are focused into the gas target at a small angle relative to each other. HHG occurs efficiently only in the region where these pulses overlap constructively and with the correct combined field characteristics. The generated harmonics may then propagate in a direction bisecting the angle of the input beams, or in other specific directions depending on the phase-matching conditions for the non-collinear interaction, allowing spatial separation from the fundamental beams and potentially from harmonics generated by each beam individually.

Both methods exploit spatial separation to isolate SAPs, offering an alternative or complement to purely temporal gating techniques. However, they require precise control over the pulse-front tilt or the non-collinear angles and overlap.

2.9 Generating Circularly Polarised High Harmonics

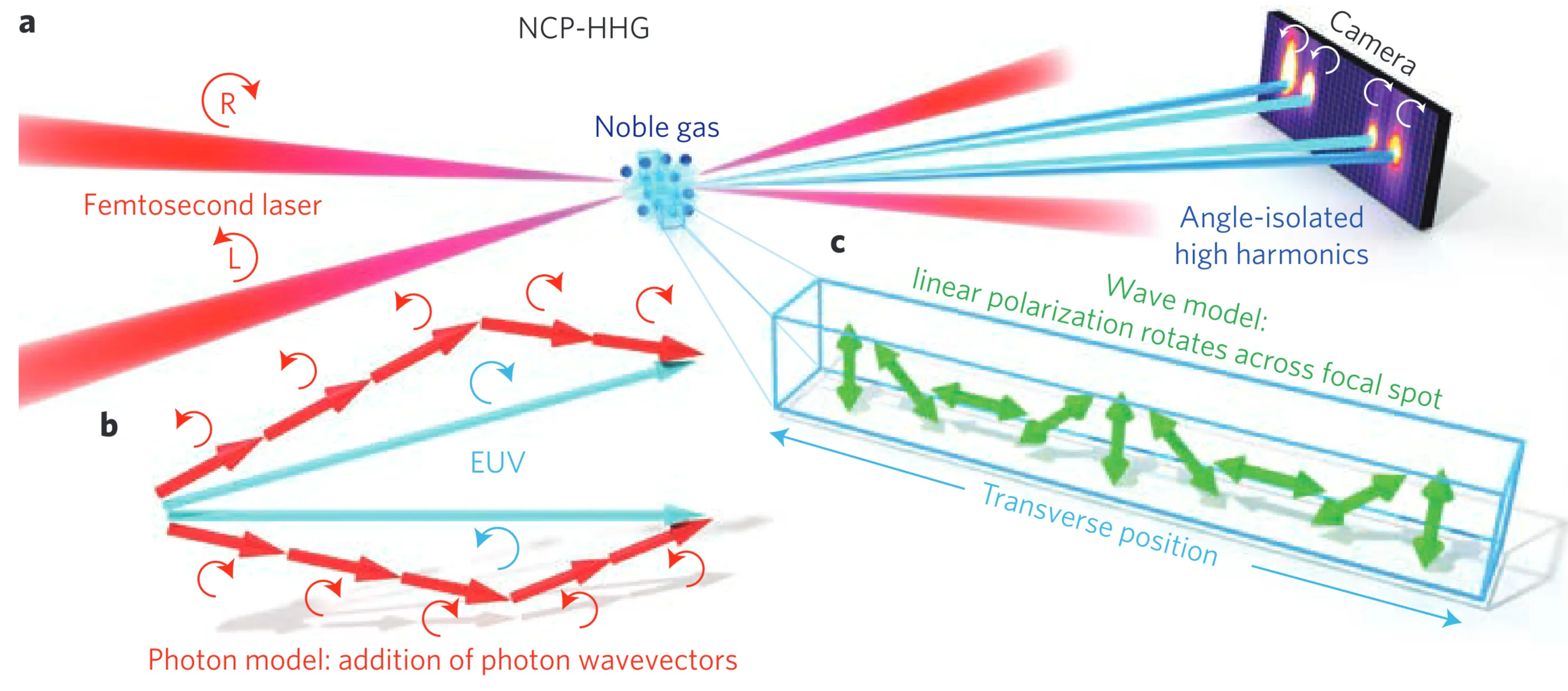

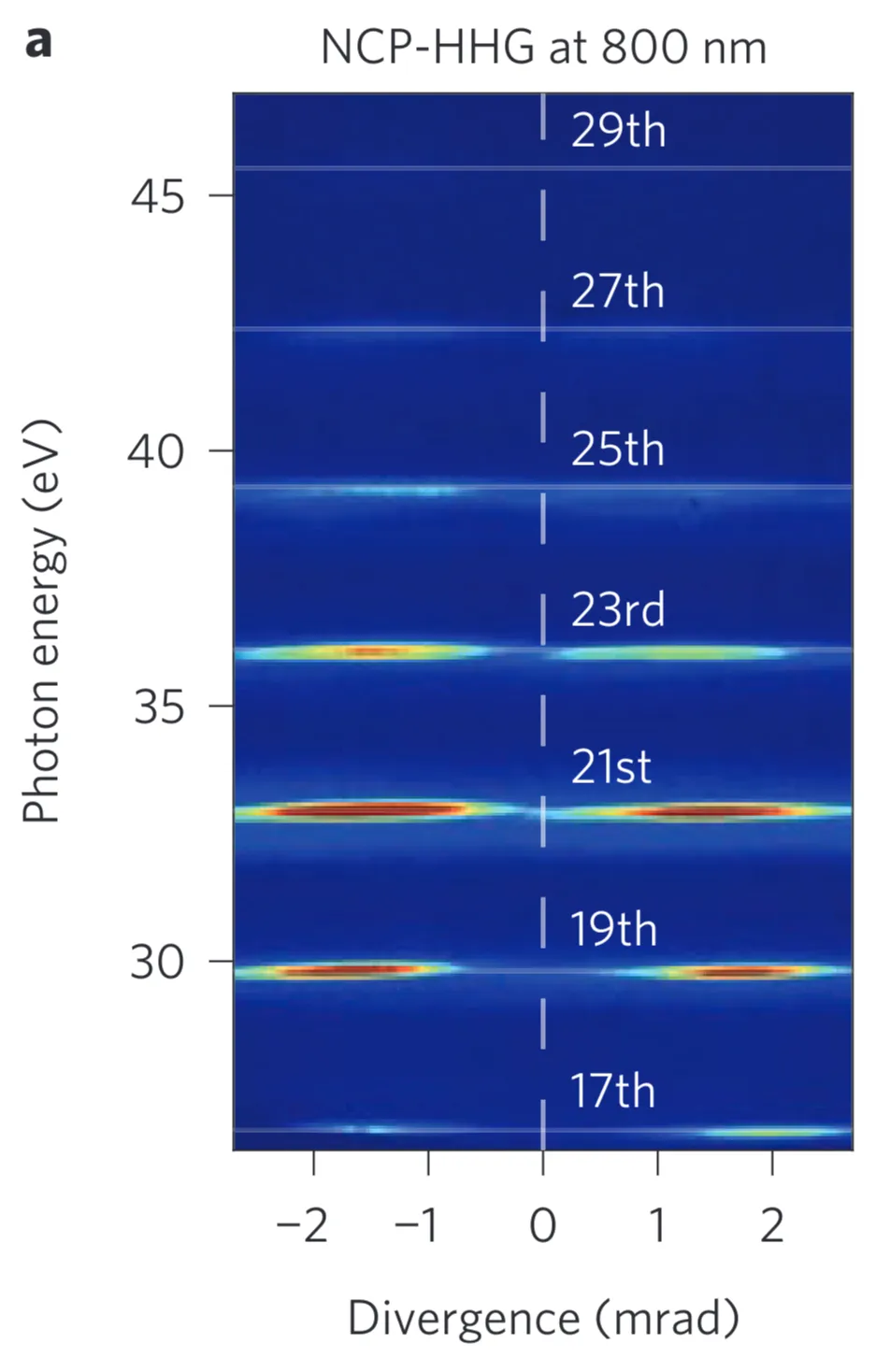

Based on the paper "Non-collinear generation of angularly isolated circularly polarized high harmonics", one method to generate circularly polarised high-order harmonics involves non-collinearly focusing a left-circularly polarised (LCP) and a right-circularly polarised (RCP) femtosecond laser beam into a gas target. This approach offers several advantages compared to some other methods for generating circularly polarised XUV light. Firstly, it can use a single-colour driving laser (split and then recombined), which helps in maximising the achievable cutoff photon energies compared to multi-colour schemes that might have lower effective peak fields. Secondly, due to the specific non-collinear geometry and selection rules, the generated circularly polarised high harmonic radiation can be angularly isolated from other signals. Lastly, the crossing angle between the two driving lasers can facilitate this angular separation of the desired harmonic beams without necessarily requiring a spectrometer for selection if the angular separation is sufficient.

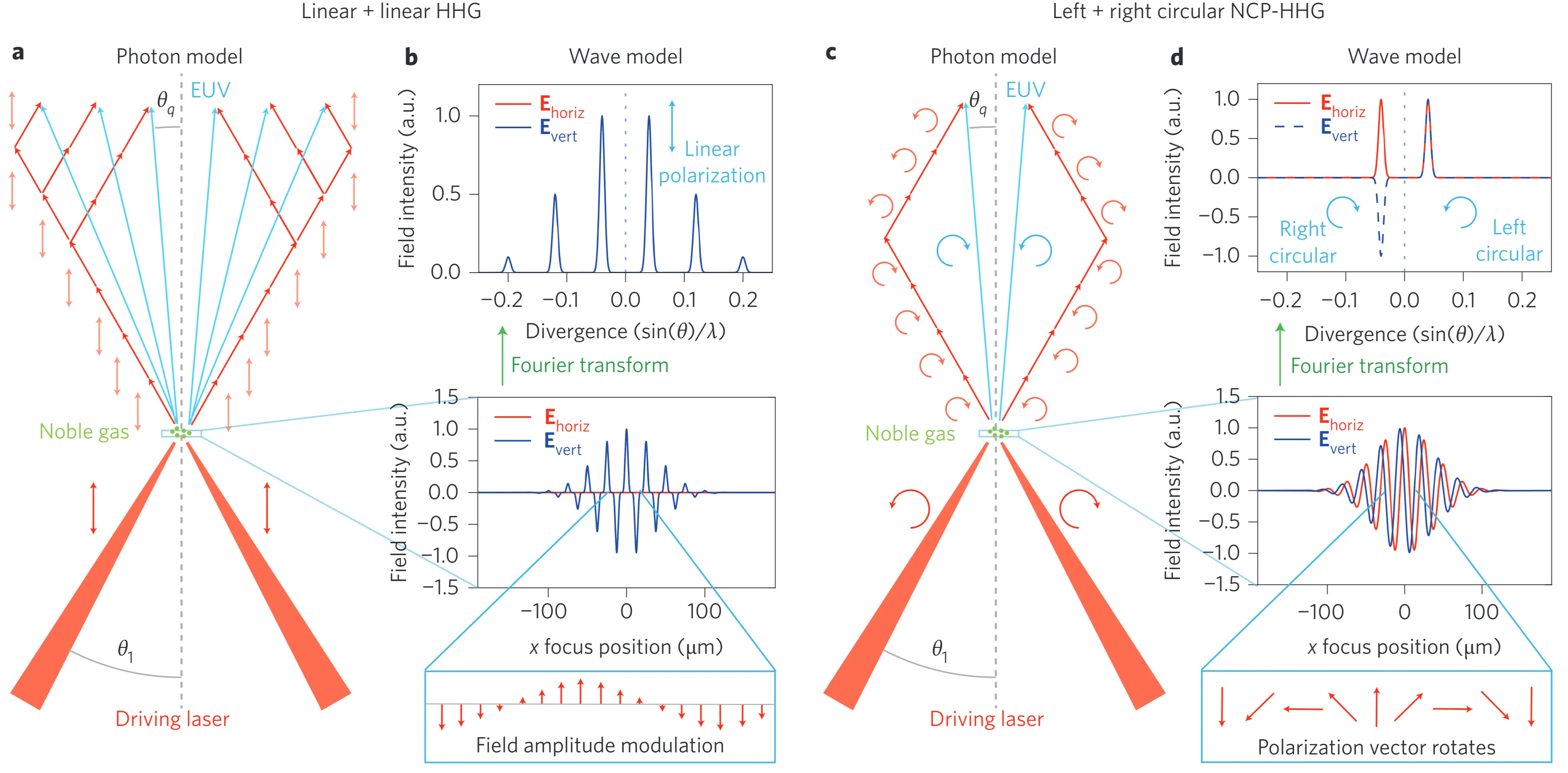

The non-collinear HHG process with circularly polarised drivers can be understood from two perspectives:

- Photon picture: This method is governed by selection rules that take into account the conservation of energy, parity, linear momentum (phase matching), and spin angular momentum. For HHG, the atom absorbs

photons from the first beam (say, LCP, helicity ) and photons from the second beam (RCP, helicity ) to emit a harmonic photon of order with helicity . Conservation of spin angular momentum requires . For instance, to generate an RCP harmonic ( ), one possible combination is LCP photons and RCP photons. This dictates specific combinations of photons from each beam for each harmonic order and helicity, leading to distinct emission directions due to linear momentum conservation in the non-collinear geometry (see figure (a) and (c) in the source). - Wave picture: The key is that although each individual driving beam is circularly polarised (for which HHG is strongly suppressed), in the region where the two counter-rotating circularly polarised beams cross, their superposition can create a total electric field that is locally linearly polarised, provided their amplitudes are equal. The orientation of this local linear polarisation, however, rotates in time with a frequency related to the fundamental. HHG is efficiently driven when this local field is linear. This can be thought of as a "rotating polarisation gate." In contrast to the interference pattern formed by two co-polarised or linearly polarised beams (figure (b) in source), the crossing of two orthogonally (counter-rotating) circularly polarised beams (figure (d) in source) does not produce a stationary spatial intensity interference pattern in the crossing plane, but rather this rotating linear polarisation.

For the mixing of linearly polarised laser beams in a non-collinear geometry, a constraint for generating a harmonic of order

Both driving beams need to be precisely overlapped both in time and space for the combined field to achieve the necessary characteristics for HHG, as individual circularly polarised beams are very inefficient at harmonic generation. The scheme typically produces two XUV beams for each generated harmonic order that satisfies the selection rules, with these two beams being circularly polarised with opposite helicities and emitted at symmetric non-zero angles with respect to the bisector of the driving beams.